Artificial turf, counterfeit money, fake noses, fake moustaches, fake... um... other body parts... and... fake baseball games?

All of them are out there, and while some of those things may in varying degrees provide some entertainment value (some of them

obviously more than others), there's nothing funny or worthwhile about fakes and fraud in our quiet little backwater of a hobby.

Every genre of collectible antiques -- art, silver, glass, furniture, sports memorabilia, you name it -- is plagued at least occasionally

by fakery and fraud. Sometimes it begins innocently enough, with reproductions or knock-offs made for sale as such to collectors who

can't afford the often exorbitantly priced originals, but which wind up being offered for sale as originals, by dealers who may themselves

be ignorant of their wares' repro origins, or in too many cases by unscrupulous dealers fully aware that what they have is not the real

McCoy.

The relatively young but explosively expanding hobby of sports memorabilia collecting is fraught with fakery, particularly in the area

of vintage baseball cards. Happily, the tabletop baseball game hobby has been relatively free of these sorts of shenanigans. Board

games, with their many parts and pieces, are a complicated, labour-intensive thing to reproduce -- and few games command prices

high enough to justify the time and trouble of faking one. Unfortunately, there are exceptions.

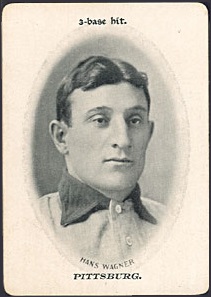

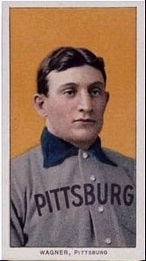

Multiple examples of at least twenty different baseball cards have sold on multiple occasions for more than $100,000. each,

topped by the famous circa 1910 T206 Honus Wagner, with dozens of other cards regularly selling for more than five figures. The

astronomical prices earned by the most desirable baseball cards extends to a handful of old baseball card games and individual cards

from those sets. The cards by themselves are fairly easy and cheap to fake -- monochrome images on pasteboard -- and even without

their boxes and other playing pieces, the originals are much in demand among well-heeled card collectors as well as game collectors.

It often takes an experienced eye to discern the difference between one of these antique game's original cards and a modern

reproduction meant to deceive a gullible buyer. Collectors should be wary and well informed when considering the purchase of cards

purporting to originate from the 1906 "Art Series" editions of Fan Craze (designated "WG2" and "WG3" in the American Card Catalogue),

1913's Base Ball ~ The National Game ("WG5"), the Tom Barker Baseball Card Game of 1914 ("WG6"), All Star Card Base Ball from

1914 ("WG4," known to card collectors as "the Polo Grounds game"), the Great-Mails Baseball Game of 1923-24 ("WG7"), and The

National Game ("WG8") of 1936 made by S&S Games Co. Complete sets of each of those games routinely fetch four figures at auction,

in many cases well more than five, with some individual cards from some of those games frequently going for well over $1,000. by

themselves. There are other, even older, baseball card games with comparable market value, but those cards are elabourate,

multi-coloured affairs, much more difficult to reproduce and their reproductions easier to detect. Have some hands-on familarity

with examples from these sets, and buy only from a trustworthy source, if you're thinking of forking over a substantial sum for

any of those, or for any high-priced baseball card. The card hobby is infested with sophisticated fakery. We recommend the

collecting community at Net54 for both a primer and advanced details on what to look out for and beware of.

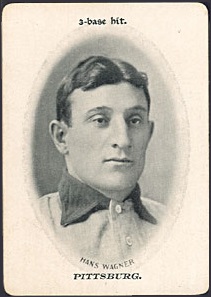

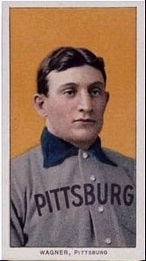

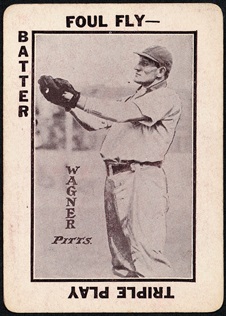

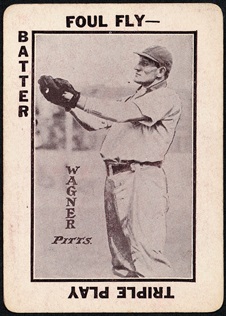

Four Wagner cards from five different sets: |

|

Wagner appears in, left to right, Fan Craze (1906), the T206 series of tobacco cards (1909-11), All Star Card Base Ball (1914),

and, at far right, the nearly identical Baseball ~ The National Game (1913) and Tom Barker Baseball Card Game (1914). |

Honest reproductions of baseball card games are usually marked as such, and in their own original form are not to be lumped in with

outright fakes. Larry Fritsch Cards has for years been producing honest, handsome repro sets of many of the games cited above, but

scammers have often tried to palm them off as originals, usually after altering the cards to erase printed evidence that the cards were

latter-day reproductions.

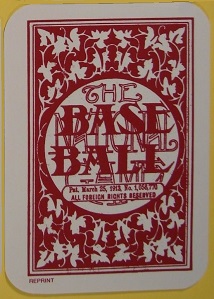

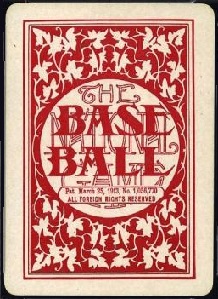

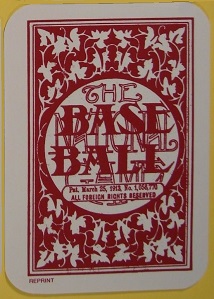

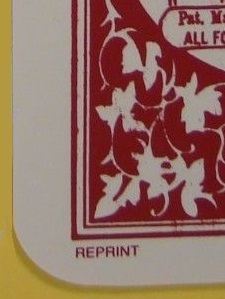

Card backs from original and repro editions of Baseball ~ The National Game: |

|

Left to right, card from original 1913 set of Baseball ~ The National Game ("WG5") made by National Base Ball

Playing Card Co, card from 21st-century repro set by Larry Fritsch Cards, and detail from Fritsch edition,

forthrightly identifying card as "reprint." Note also the diagnostic difference in the corner shaping. |

|

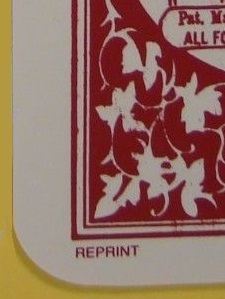

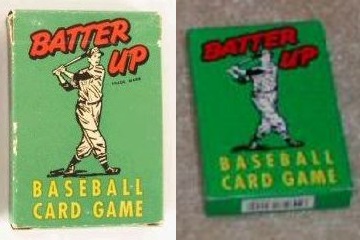

Batter Up Baseball Card Game, Ed-U-Cards' 1949 original version

(shown at far left) of their hugely popular 1957 Baseball Card Game,

was reprinted by an unidentified entity sometime in the late 1990s

or early 2000s. Nearly identical to the original in almost every other

detail, the repro version (near left) is easily identified by the absence

of the small print indicating "trade mark" just below the game's title

on its flip-top box, and of course by the presence of the UPC bars on

the box's bottom flap.

|

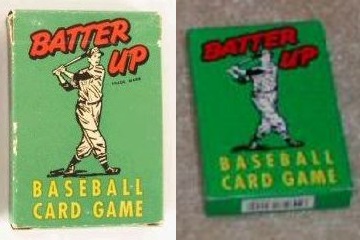

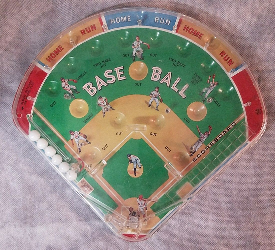

| Another repro often mistaken for the original

is Schylling's 2001 remake of Baseball Pinball

Game. Although there are significant, obvious

differences between the boxes and backsides

of the remake and the game produced around

1960 by Marx, both are freqently offered for

sale on-line without the box or without photos

of the backside. The Marx game, seen at left,

displays "Base Ball" in a font divided by a

red hairline, nine stanchions supporting the

"warning track" scoring area, and averages

about $15.-$20. at auction. The Schylling

repro, at right, has "Base Ball" in a subtly

different font decorated with blue dots, six

outfield stanchions, and averages about $5.

at auction.

|

|

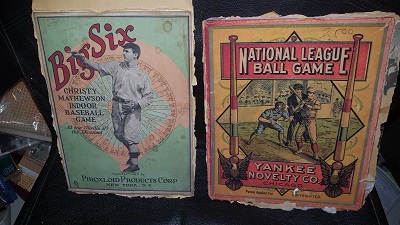

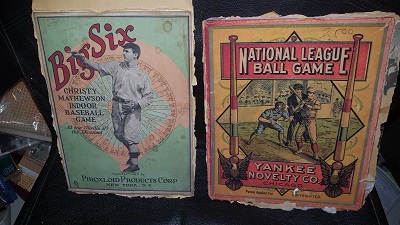

Here's some garbage that made us do a double-take and had us briefly beflustered, but which quickly revealed itself as totally bogus:

These fake antique game-box lids showed up on eBay in January 2018. The least little bit of research would have demonstrated that

they are not authentic. All anyone needed to know was that an original Big Six box is a big 22 1/2 x 16", while an original National League

Ball Game box is a just slightly smaller 5 1/2 x 4 1/2". The second pair displays similarly wild inconsistencies in size, and several other

details in all four lids make it further inarguable that all four are outright fakes. Yet someone deluded themselves into paying more than

$320. for this set of worthless decorations. Well, okay, as decorative pieces, not entirely worthless. Maybe eight or ten bucks for the set.

These fake antique game-box lids showed up on eBay in January 2018. The least little bit of research would have demonstrated that

they are not authentic. All anyone needed to know was that an original Big Six box is a big 22 1/2 x 16", while an original National League

Ball Game box is a just slightly smaller 5 1/2 x 4 1/2". The second pair displays similarly wild inconsistencies in size, and several other

details in all four lids make it further inarguable that all four are outright fakes. Yet someone deluded themselves into paying more than

$320. for this set of worthless decorations. Well, okay, as decorative pieces, not entirely worthless. Maybe eight or ten bucks for the set.

|

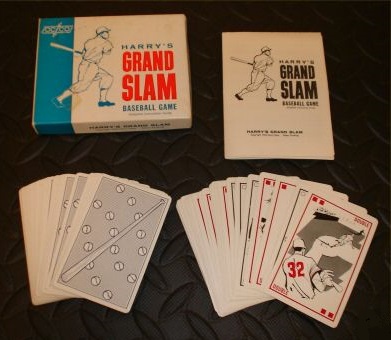

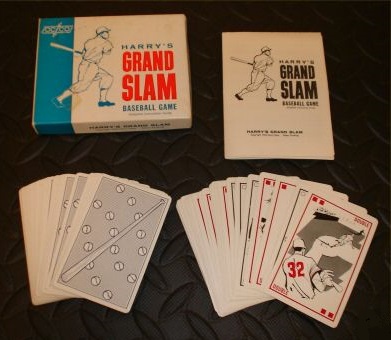

One disturbing, if not terribly costly, development was a reproduction set of

Harry's Grand Slam Baseball Game, originally made in 1962 by the Olympic

Card Company. Heirloom Games and Out Of The Box Publishing turned out

a rather too-faithful repro set of the 1962 original in 2005, unfortunately

declining to mark anywhere on the cards or the box that it was a repro. The

two versions are identical in every respect, so the repro is indistinguishable

from the original. The lone and feeble upside to the situation is that neither

original nor repro generally sells for more than about $10.-$20. Presumably

well-intentioned in reviving the obscure Harry's, Heirloom / OOTB gain no

advantage beyond basic sales from having made the duplicates, but it was

grossly irresponsible of them to make the reprint identical to the 1962 issue.

Uninformed or unscrupulous vendors frequently peddle the repro issue as

"vintage," and as a result, the market value of the original has nose-dived.

At right, a complete example of Harry's -- an authentic 1962 original,

or a 2005 reproduction? We can't tell, and neither can you.

|

|

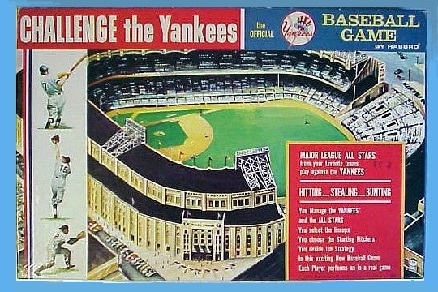

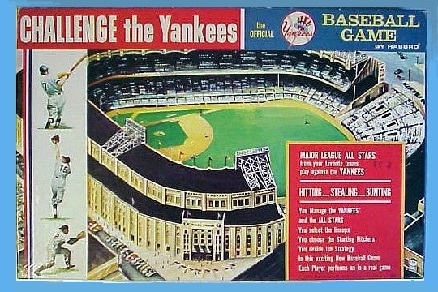

| At left, the potential subject of exactly the same problem,

but on a much grander scale -- Challenge the Yankees,

originally published by Hasbro in nearly identical 1964 and

1965 editions. One of the most avidly sought post-War

games, collectors have paid, over the past fifteen years,

an average of more than $600. for examples, several times

going well into four figures, many of those games less than

complete and most in somewhat distressed condition.

The game's designer, Roger Franklin, retained the rights

to his creation, and his family announced in 2017 that they

would be producing a repro edition of "CTY" -- faithfully

identical to the original Hasbro issues, with no markings

whatsoever to distinguish the new games from the 1960s

originals. Arguably, Franklin has (and should have) the

right to do whatever he wants with his brainchild, but had

the project proceeded as described, it would have been a

major disservice to the hobby -- an insult to collectors who'd

made a major investment in the original editions, and an

open invitation to rampant fraud. Fortunately, crowdfunding

efforts to launch the imitation fell short of their goal, thanks

in no small part to their marketing department's arrogant,

smugly dismissive attitude toward criticisms and suggestions

from the very community they'd targeted as their customers. |

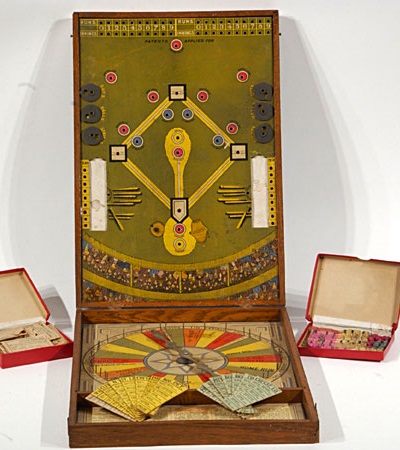

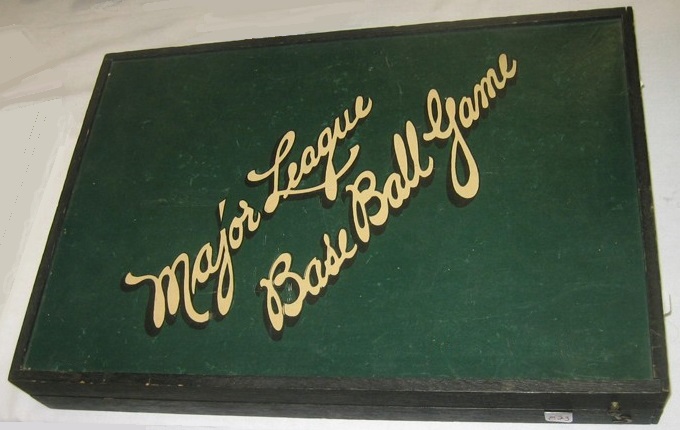

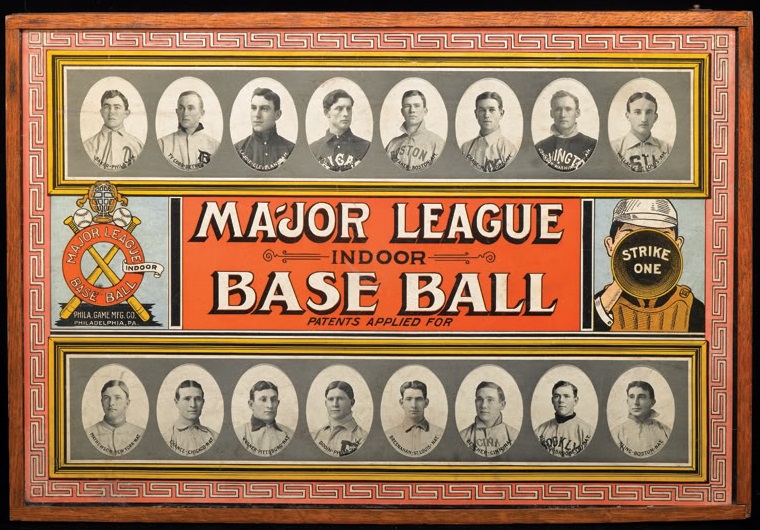

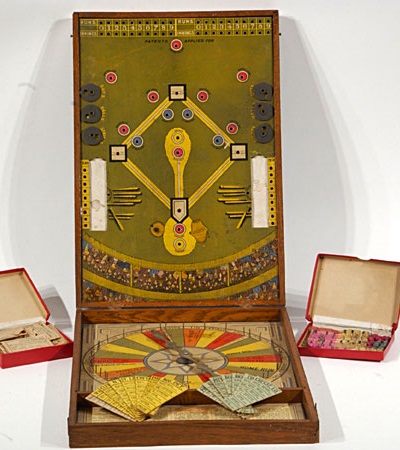

A full-fledged boardgame vulnerable to ouright fakery is Major League

Indoor Base Ball, produced by Philadelphia Game Mfg Co in 1912 and '13.

A second edition of the game, retitled Major League Base Ball Game, was

turned out from 1913 through 1926. The two editions are virtually identical

but for their box lids, and therein lies all the difference. Both games are

beautiful, sturdily-built things, both of them in demand among collectors.

But while nicer examples of Major League Base Ball Game, with its

relatively plain dark green cover, have averaged just under $300. through

dozens of on-line sales and auctions over the last fifteen years, examples

of its predecessor, Major League Indoor Base Ball, in similarly nice

condition and sporting its elabourate colourful cover featuring Carl Horner

portraits of sixteen star players of the day, have averaged $3,100. over

that same span. Although the difference would be evident at a glance with

a hands-on examination, it would be a simple matter for a scam artist to

slip a photocopy of the Major League Indoor Base Ball cover into the lid

of a Major League Base Ball Game box and produce a convincing photo

for an on-line auction. We've seen it attempted.

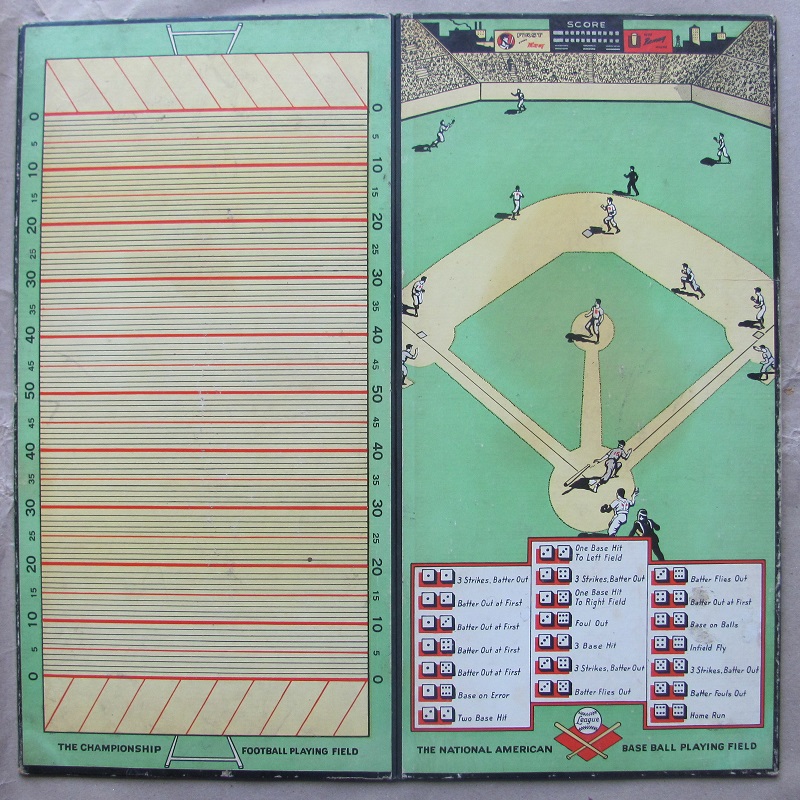

Below, the box lids of Major League Base Ball Game and Major League

Indoor Base Ball; at right, the dazzling interior of either version, showing

the hinged wooden box, the ornately illustrated gameboard / playing field,

the enormous chrome spinner, roster strips, and the twin parts boxes

holding marker pegs and other game paraphermalia. |  |

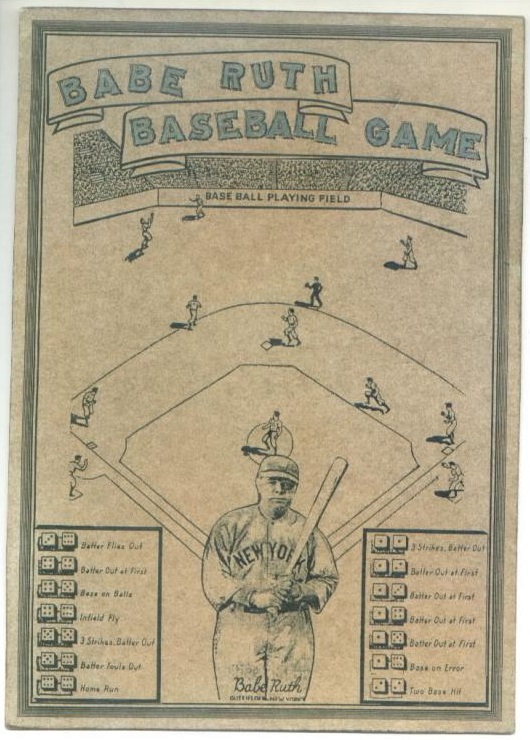

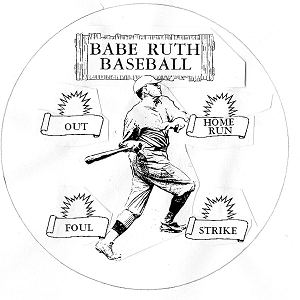

This brings us to a whole series of closely-related fakes that prompted this article in the first place. These are all what are known

in the hobby as "fantasy pieces" -- modern-day creations masquerading as antiques that never actually existed. We first saw one from

this particular series in 2004, and it and several spin-off variations have been popping up every few years ever since. They're all clearly

the work of the same hand, they're all inevitably billed as hailing from the 1920s or '30s, and they're all screamingly obvious as fakery.

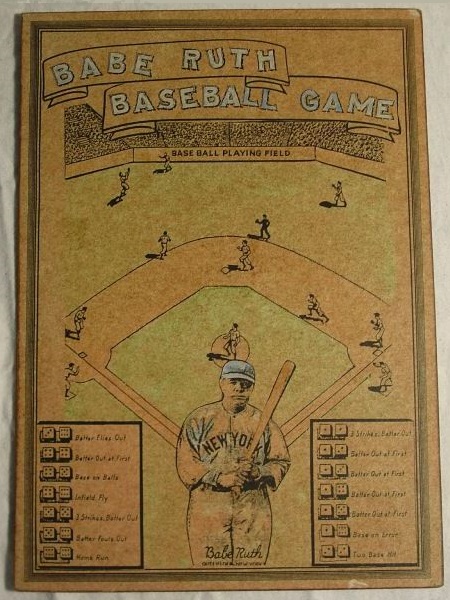

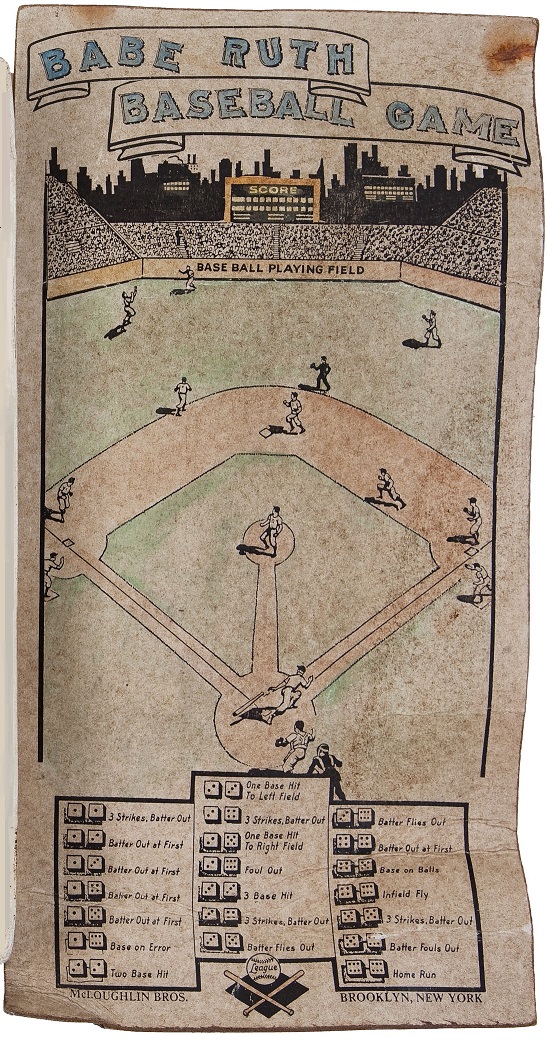

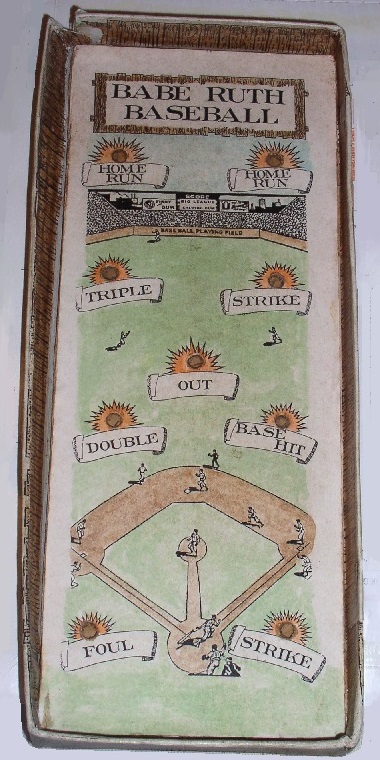

In the perp-walk below, we'll identify several varieties of a little horror calling itself "Babe Ruth Baseball Game". At least seven elements

of the game board, seen below at right, frantically wave red flags and sound claxons to alert one and all that it's unequivocally a modern

fantasy piece.

The most obvious points are the illustrated playing field and dice-combination results, both of which are photocopied from either one of

two popular Parker Brothers baseball games shown below, top left -- the 1948 edition of Double Game Board, or the identical board from

their 1957 edition of Baseball Football and Checkers. The Parker games are plentiful and relatively cheap to obtain. The rearranged

table of dice combinations, showing the diagnostic shadowed dice and professionally handwritten italic font of the Parker boards, is

laughably switched around, placing the last third of the 21 possible results first, the first third last, and omitting the middle third -- 2/3, 2/4,

2/5, 2/6, 3/3, 3/4, and 3/5 -- entirely. In contrast to the lettering in the results table, the letters in the banner giving the game's title are

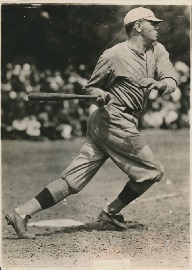

crude and amateurish. The image of the Babe himself is an iconic one, well known to collectors from a late 1920s "exhibit card," easily

available on-line or in any number of books. The signature printed across the bottom of the image is not an autograph, but displays

as printed on the exhibit card, which used the same font for all 69 cards in the set. The overall image shows the black-&-white

"posterization" effect due to photocopying a grey-toned photographic image. Lastly, it's worth noting that Parker Brothers' company

records show no evidence of their ever having produced any Babe Ruth game, nor of ever having licensed the mechanic or graphics of

Double Game Board to any other manufacturer.

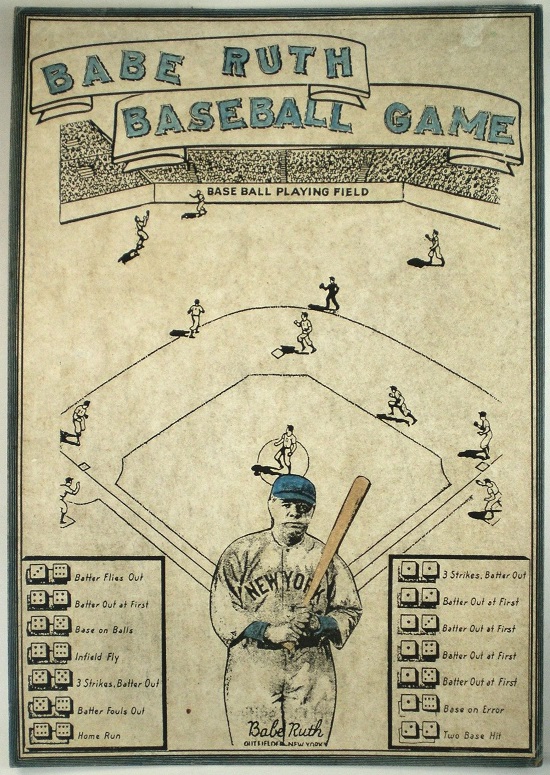

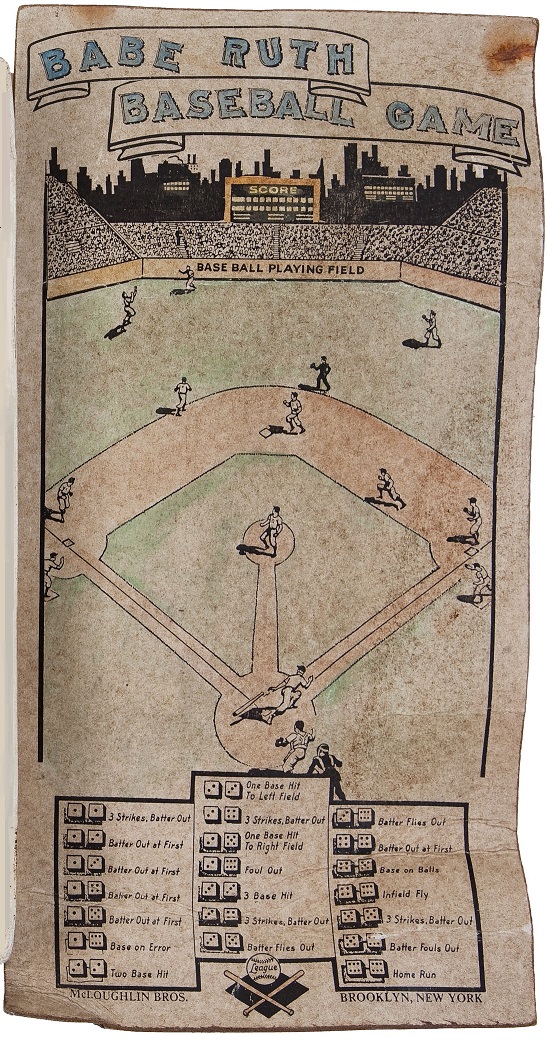

Three other variations of this board have been spotted: that shown

above at lower left adds colour to the Babe's cap, sleeves, and bat,

that above at lower right to the entire board, and that directly at right

provides an enhanced city skyline and a new rearrangement of the

dice results on a longer board, along with a ludicrous publisher credit

and more artificial aging (some deliberate crumpling, a few tea stains,

and gently baked in an oven to a delicate golden brown). All three

above measure roughly 13.5 x 9", the fourth at right about 18 x 9".

Subtle differences between each version, in colour coverage in the

title lettering and in the Babe's cap, along with the apparent lack of

half-tone printing dots in the colour areas, strongly suggest each

version was coloured by hand, which would rule out any possibility

these were mass-produced in even very limited quantity by any real

game publisher -- let alone by McLoughlin Brothers, as the credit line

at the bottom of this variation would have us believe. McLoughlin

were the pre-eminent publishers of boardgames through the second

half of the 19th century, finally eclipsed by 19th-century rivals Parkers

and Milton Bradley as the 20th century dawned (our history of the

company and their dozens of graphically gorgeous, painfully simplistic

baseball games is here). It's obviously impossible for Parkers' 1948

graphics to have appeared on a pre-1920 McLoughlin game. And

while McLoughlin did have a printing factory in Brooklyn, their main

offices were always in Manhattan, and whenever their games carry a

city-of-origin credit, it's always "New York" or "N.Y.," never "Brooklyn."

We'd long hypothesized that the first three fake "Babe Ruth" games

we've shown here were never intended to fool anyone or to defraud a

na´ve buyer, but were, instead, nothing more than a design project by

some high-school or middle-school art student, which escaped into

the wild in a yard sale, and eventually were put up for sale on-line by

uninformed vendors.

However, the McLoughlin credit on the fantasy piece at right, which

turned up at a major auction house in 2013, gives us pause. Parker

Brothers and Milton Bradley remain household names, so if some kid

was going to add a publisher credit to their little art project, one of

those two famous companies, or no credit line at all, would seem to be

a likely choice. Somebody would have to have some solid knowledge

of collectibles and antiques, though, to know anything of McLoughlin

Brothers, which in turn sort of presupposes some awareness of the

high prices paid for McLoughlin products, and that makes the item

at right a little bit suspicious...

|  |

|

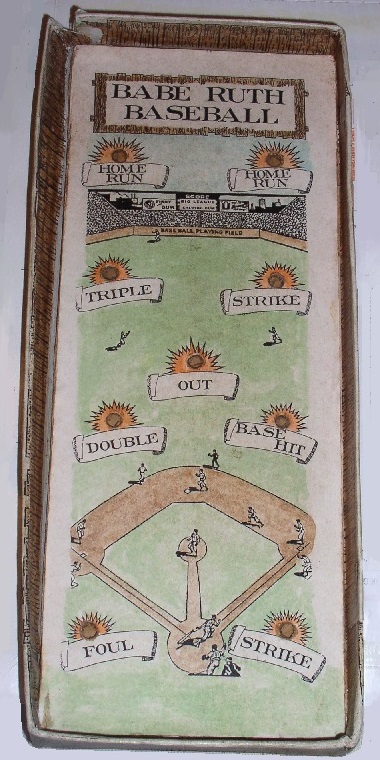

Whoever created these things, you have to give them points for

their efforts at recycling. Another fantasy piece surfaced, using

many of the graphic elements seen in the boards above and from

the same sources whence those were copied. In this "Babe Ruth

Baseball Game," the title banner is identical to that in the above

examples, and the bleachers and the cityscape beyond, as well as

the crossed-bats logo at the bottom, are all taken from the same

Parker Brothers game that was sourced for the playing field. The

image of the Babe is another iconic one -- this one might be drawn

by hand from the photo source, bringing us back to our "art student"

theory -- and again the tinted portions of the board appear to be

hand-coloured.

Most tellingly, the numbered play results -- as with the incomplete

dice combinations in the first three examples -- make no sense

whatsoever -- 2, 3, 6, 7, and 8 each appear twice, redundantly,

4 and 5 just once each, and 1 does not appear at all. If this were

a spinner game, there can be no reason to have numbered the

results this way; if it were a two-dice game, which would account

for the absence of the "1" result, it would require tetrahedral dice,

unheard of in its purported era, numbered 1 through 4, and hitting

would come in at around an .833 clip, beyond the pale even for the

offense-juiced children's games of the day, with the relatively rare

triple being the most common result. Either way, it would have

been senseless for a "real" game company to have listed five of

the combinations twice and two only once.

|

The parade of phonies continues, red flags flying and jingtinglers,

gardookas, and great big electro whocarnio flooks blaring, with the

item at right. Once again using the Double Game Board graphics,

this "Babe Ruth Baseball" suggests more of an "action" game,

implying that some sort of projectile -- a marble or small puck --

is to be struck into one of the holes in the playing field, presumably

propelled by a miniature bat or flicked by a finger. It uses the same

typography as the game discussed just above, both in the title and

in labelling the results, and again appears to be hand-coloured,

although the sandlot plank fence drawn around the inside of the

box aprons is a thoughtful touch. The holes -- five to be targeted,

four to be avoided -- are decorated with spiked outlines, suggestive

of impact or explosion, a graphic device generally not seen in

cartoon illustration until the 1950s. And the holes themselves

are not die-cut, as they would be in a game made by a legitimate

publisher, but appear to have been gouged out with the use of

a dull screwdriver or a grapefruit spoon. In a hilarious fit of

desperation, the vendor claimed this was a McLoughlin Brothers

product. If the abyssal distance in quality between these

fantasy pieces and any McLoughlin product is not convincing

evidence that these are fakes (again, compare the McLoughlin

line at our page here), remember that McLoughlin had basically

gone out of business by 1920, just before the Babe had really

even established himself as baseball's star slugger.

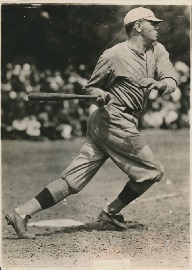

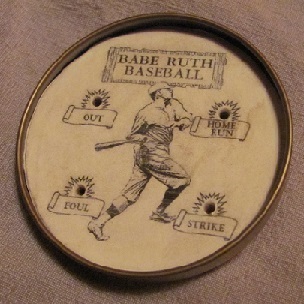

The topper, so to speak, may be the ridiculous item seen below,

which showed up on eBay in the summer of 2017. The vendor had

the gall to claim this 2 7/8"-diameter gimcrack was a "1920" product,

all the more valuable because it pictured the Babe as a Red Sox

slugger and was partly made of an "early plastic."

In fact, the picture is of the Bambino, crudely photocopied from

the photo shown farther below, which was taken in 1918. Up until

1920, the Babe was best known as one of the very best young lefty

pitchers in baseball. It wasn't until 1920 that he became recognized

as baseball's prepotent offensive force. But he did it as a Yankee,

Boston having sold him to New York at the end of the previous year.

That he would have endorsed a game that pictured him as still a

member of the Red Sox seems a dubious notion.

What really convicts the piece below as inauthentic, though, are

the graphical elements that repeat from the item directly at right,

which features other elements already repeated there from the

1948-and-later Parker games. There's the title banner, and the

clumsy font labelling the anachronistic "impact" spikes. Again,

the target holes are roughly hacked into the surface, rather than

die-cut, and there's no glass cover to keep the BB in play.

The plastic jar-lid liner begs for attention as well. The basic

chemical principles of plastics were known as long ago as 1839,

but the development of modern plastics for practical use took

nearly another century.

|  |

|

Modern synthetic plastics, ubiquitous and omnipresent today in countless forms, were not really even

developed until World War II -- and definitely not in common use, certainly not for anything as trivial

as toys, until after the war. So the claim that this item, with its plastic-lined jar-lid, dates from 1920 is

patently ridiculous.

The pathetic punchline to this joke is that someone was suckered into shelling out over 360 bucks

for this silly thingamabob on eBay in August 2017. Ouch. "But wait -- there's more!" Several weeks

later, the buyer tried to turn it around on eBay at $1,800. -- $1,800.! No takers, happily, but then, in

March -- turpem dictu! -- it did sell for something close to $800. How often is a sucker born?

As merely a preposterous fake, it was as amusing as it was annoying, but that somebody profited

big-time with it (well, big-time by the standards of our own minuscule budgets) got us kinda riled up.

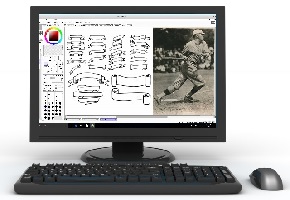

We decided to demonstrate how easy it was to have created this nasty little thing. None of us in the

Baseball Games front office have any experience with craft projects or fakery, so if, with negligible skill

and just minimal time and effort, we could come even reasonably close to duplicating the cursed object

above, it's something anyone could do. In a moment, the results of that trial. Your comments on our

project are welcome at our Forum.

Ingredients needed for this recipe: 1 jar lid, internet access to clip-art graphics, 1 photo of the Babe,

razor knife, printer, copy machine, white-out and a brush, tea, oven, cardboard, glue, awl, 1 BB.

|

The lid itself, in fact, was the only difficult thing to replicate. The lid used in the fake dexterity game may actually have some age to it

-- which doesn't for a moment mean the fake game is anywhere near as old as it pretends. You, we, almost everyone, has some old jar

of something in the garage or the basement. We wasted a few man-hours strolling supermarket aisles in search of the closest match

we could find, thinking the lid came from a jar of something edible. You and we have all seen a million lids sort of like this on tens of

thousands of food products, the plastic liner being the only anomalous feature. That modern liner aside, though, the lid is a bit unusual

in that it has no writing, the sides are flat, with no incised screw-top lines, ribbing, or dimples, nor, most notably, does it show the four

crimped spots at the rim that are present on about 95% of modern food-jar lids. You can find dozens of food products with lids exhibiting

four of the five key elements -- 2 7/8" diameter or thereabouts, gold color, no writing, no indentations on rim, no crimping -- but good luck

finding one that sports all five, let alone one with a plastic liner.

The creator of the fake didn't have to match anything, though -- he just grabbed a lid at random, while we were trying to find a needle

in a haystack. It dawned on us that the lid could have come from a jar -- or can -- of anything, not necessarily food. Maybe it came

from a jar of pills, or skin cream, or some commonplace middle-school thing like a jar of school paste or tempera paint, or maybe it's the

bottom half of a tin of shoe polish. If you can match it perfectly, let us know what it belongs to. And see if you can guess the source of

the lid we (not keen on wasting more time in search of a perfect match) wound up settling for. We'll reveal it at the end of this article.

The same sort of trouble is inherent in matching the title border, the little banners, the impact blasts, and the type face. There are

a million bazillion examples of each of those things in the thousands of clip-art sites on the internet, but again, disinclined to waste

too much time and effort, we contented ourselves with just a fair approximation of the graphics. We're sure you can get a closer match

if you want to try replicating the thing yourselves.

The next step, then, is to find those graphics on the web, plus that 1918 photo of the Babe. Save the images, calculate the size they

should be on the fake game, and either reduce them to the proper measurements in your computer graphics programme, or just adjust

their proportions to the correct sizes relative to one another. Print 'em out, cut 'em apart, and assemble them as they appear on the fake.

Use illustrator's white-out (like Pro White or a white gouache) or your computer graphics programme to mask the cut-lines and any stray

black or grey marks on the scan. Reduce that "paste-up" (as they say in the graphics-and-printing biz) to the final correct size on your

computer or on a copy machine. Print out several copies -- you'll probably need to do some trial-&-error experiments in the next step.

Take a break and fix yourself a lovely cup of tea. Real weak tea. Soak one of the print-outs with the tea. Strengthen the tea a bit

and soak another copy with that darker mix. Try a few different shades. Let 'em dry. Now put 'em on a cookie sheet or something and

toss 'em in the oven at a low bake for a minute or three. Actually, we're writing this as Christmas approaches, and it occurred to us that

some watered-down dregs from a mug of hot cocoa might also be worth a try as a colouring agent, so that's what we used.

While you're waiting, cut out a piece of corrugated cardboard, or several pieces of shirt-box / cereal-box cardboard, to the diameter

of your jar lid.

Smear a very thin coating of glue or rubber cement on the cardboard disc, then center your tea-coloured playing surface over it and

attach it. Give it a few minutes to dry, then punch holes in the appropriate spots using an awl (there's probably one in your Swiss Army

knife), or a knitting needle, or, if your cardboard is fairly flimsy, even a toothpick might do the trick. Ream the holes to a workable size.

Once you're satisfied they'll stop, but not trap, the BB, snap the whole disc arrangement into your jar lid. Drop in a BB. You're done.

Now photograph your handiwork, auction it off on eBay, and collect 300 bucks. No, wait, sorry -- don't do any of that. It would be

evil and disgusting and you'd be a total creep who shouldn't be able to look at himself in a mirror.

We'll reveal now that our lid is from a large decorative scented candle, and that was our biggest, almost only expense -- we got one

on sale for about seven bucks. Beyond that, we already had the computer and printer/scanner, obviously, but if you don't have your own,

you can achieve the same results with only a few additional steps by using the copy machine at your local library, which should cost you

something like 15 cents a copy. Kerm and Butch here in the Baseball Games front office already had the art supplies, but if you don't

have those things on hand, the white-out is cheap (even typists' correction fluid might do in a pinch) and a sharp pair of scissors and

a steady hand can substitute for the Xacto knife. Kerm's wife provided the tea, Win's grandkids provided the BBs.

Total cost of this project: basically the seven bucks for the candle's lid, ninety cents for the use of our library's copier while our

front-office printer was out of commission, and whatever few cents a couple of teabags or a packet of cocoa mix cost. For you, maybe

another five-ten bucks for art supplies, but household items already on hand should do well enough without incurring any new cost at all.

Here ya go, then -- the original fantasy piece on the left, our finished product on the right. Forensic examination will confirm we didn't

match it perfectly -- the plastic liner the most obvious disparity, and theirs has been worked a little harder into a state of grundginess

-- but seriously, making the thing from scratch and investing minimal time and effort, did we come close or didn't we? If they'd used

the photo of our piece of junk instead of the photo of their piece of junk and made the same "1920 rarity" claim, would ours have fooled

anyone as theirs did, or not?

That was a sick sort of fun. We may update this article, not too far down the road, with another absurd fantasy piece of our own

creation. Check back in a few weeks. In the meantime -- do your research, know your stuff, don't be a sucker for a scam!

|

|

These fake antique game-box lids showed up on eBay in January 2018. The least little bit of research would have demonstrated that

they are not authentic. All anyone needed to know was that an original Big Six box is a big 22 1/2 x 16", while an original National League

Ball Game box is a just slightly smaller 5 1/2 x 4 1/2". The second pair displays similarly wild inconsistencies in size, and several other

details in all four lids make it further inarguable that all four are outright fakes. Yet someone deluded themselves into paying more than

$320. for this set of worthless decorations. Well, okay, as decorative pieces, not entirely worthless. Maybe eight or ten bucks for the set.

These fake antique game-box lids showed up on eBay in January 2018. The least little bit of research would have demonstrated that

they are not authentic. All anyone needed to know was that an original Big Six box is a big 22 1/2 x 16", while an original National League

Ball Game box is a just slightly smaller 5 1/2 x 4 1/2". The second pair displays similarly wild inconsistencies in size, and several other

details in all four lids make it further inarguable that all four are outright fakes. Yet someone deluded themselves into paying more than

$320. for this set of worthless decorations. Well, okay, as decorative pieces, not entirely worthless. Maybe eight or ten bucks for the set.