Tabletop baseball games, and sports-themed games in general, occupy a small and often overlooked

niche for game players -- "gamers" -- and collectors of antiques and sports memorabilia. But myriad

tabletop versions of baseball still thrive in production, and a variety of amazingly detailed, sophisticated

tabletop baseball games are avidly played by thousands, with a substantial and growing number of

serious collectors chasing antique and vintage games.

Through the years, few themes have generated the production of as many different board games

and card games as has baseball. "Home" and "indoor" versions of baseball actually pre-date the

1869 inception of baseball as a professional sport, patents for tabletop action games having been

issued in 1867 and 1868. And at auction, few games in any genre have achieved the prices paid by

collectors for some of the oldest and rarest baseball games still in existence.

Today, tens of thousands of enthusiasts play sophisticated baseball simulation games, whether

on their tabletops or their laptops -- the most popular baseball boardgames also being available in

computer versions. Even those unfamiliar with the entire concept have probably heard something of

Strat-O-Matic or APBA and know someone who plays those or similar games. Rare is the boy of

the baby-boomer generation who wasn't well acquainted with one or both of those, or Ethan Allen's

All-Star Baseball by Cadaco, or Ed-U-Cards' little Baseball Card Game, or one of the many

varieties of Jim Prentice Electric Baseball or Tudor's slightly zany Tru-Action Electric Baseball.

Beyond their inestimable play value, those games and hundreds of others, produced over the past

140 years by manufacturers and publishers large and small, have value as collectibles and as historical

artifacts. Victorian-era games often reflect the annually-evolving rules of baseball in its formative days.

Games of just the past century reveal a sporadic but ongoing attempt to create ever more realistic and

sophisticated approximations of baseball, while also providing, in their graphic design, a chronological

cavalcade of changing artistic styles. Some games are still plentiful even decades after they ceased

production and can be had for yard-sale prices. For others, only a handful -- in some cases, only

a single known example -- have survived, and can easily command five figures at auction. As with

any field of collectibles, age and rarity do not always presuppose demand, so while some scarce

antique games can be acquired inexpensively, a few games of much more recent manufacture, and

much more readily available, can fetch high prices.

The sheer variety of playing methods over the years and among the multitude of games produced

is astonishing. Game mechanics range from the childishly simple to the dauntingly complex, from the

elegant and ingenious to the occasionally inane, and from generic games of chance to more modern,

more scientific simulations that yield highly realistic re-creations of actual individual player performance.

Beyond their inestimable play value, those games and hundreds of others, produced over the past

140 years by manufacturers and publishers large and small, have value as collectibles and as historical

artifacts. Victorian-era games often reflect the annually-evolving rules of baseball in its formative days.

Games of just the past century reveal a sporadic but ongoing attempt to create ever more realistic and

sophisticated approximations of baseball, while also providing, in their graphic design, a chronological

cavalcade of changing artistic styles. Some games are still plentiful even decades after they ceased

production and can be had for yard-sale prices. For others, only a handful -- in some cases, only

a single known example -- have survived, and can easily command five figures at auction. As with

any field of collectibles, age and rarity do not always presuppose demand, so while some scarce

antique games can be acquired inexpensively, a few games of much more recent manufacture, and

much more readily available, can fetch high prices.

The sheer variety of playing methods over the years and among the multitude of games produced

is astonishing. Game mechanics range from the childishly simple to the dauntingly complex, from the

elegant and ingenious to the occasionally inane, and from generic games of chance to more modern,

more scientific simulations that yield highly realistic re-creations of actual individual player performance.

No examples are known to exist of the first two tabletop baseball games patented -- William

Buckley's Game Board of 1867 and Francis Sebring's Parlor Base-Ball of 1868 -- both designed

as wood-and-metal constructs that attempted to emulate in miniature the actual action of baseball.

In Buckley's game, a marble-sized ball is rolled by the mechanical "pitcher" toward a spring-activated

bat that would drive the ball into the field of play. Sebring's worked similarly, with a penny slid from

pitcher to batter and struck into play. Buckley's game probably never went into production, but

Sebring's was advertised in both Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper and Wilkes' Spirit of the Times

-- popular periodicals of the day -- as early as the autumn of 1866. With any number of further

mechanical, magnetic, and electrical variations by dozens of different manufacturers through the

years, this subgenre of "action" games has continued right into the 21st century.

No examples are known to exist of the first two tabletop baseball games patented -- William

Buckley's Game Board of 1867 and Francis Sebring's Parlor Base-Ball of 1868 -- both designed

as wood-and-metal constructs that attempted to emulate in miniature the actual action of baseball.

In Buckley's game, a marble-sized ball is rolled by the mechanical "pitcher" toward a spring-activated

bat that would drive the ball into the field of play. Sebring's worked similarly, with a penny slid from

pitcher to batter and struck into play. Buckley's game probably never went into production, but

Sebring's was advertised in both Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper and Wilkes' Spirit of the Times

-- popular periodicals of the day -- as early as the autumn of 1866. With any number of further

mechanical, magnetic, and electrical variations by dozens of different manufacturers through the

years, this subgenre of "action" games has continued right into the 21st century.

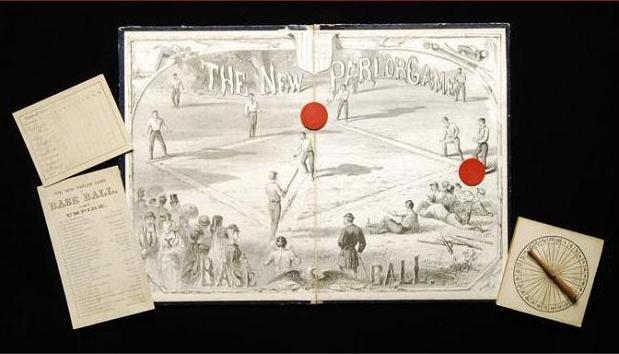

Metcalf Sumner's The New Parlor Game ~ Base Ball., produced in 1869 by Milton Bradley, is the

oldest baseball game known to survive. Featuring a lovely steel engraving of a baseball game in progress

on its gameboard and employing a small 30-sectioned spinner to determine the results, as few as three

examples of the game are extant. Manufacturers and publishers turned out more than fifty different

tabletop versions of America's new national pastime in just the 19th century alone, introducing almost

every variety of game mechanic short of computers. Baseball cardgames arrived in 1884 with Base Ball

~ A Professional & Social Game of Cards and Lawson's Patent Game ~ Base Ball with Cards.

Metcalf Sumner's The New Parlor Game ~ Base Ball., produced in 1869 by Milton Bradley, is the

oldest baseball game known to survive. Featuring a lovely steel engraving of a baseball game in progress

on its gameboard and employing a small 30-sectioned spinner to determine the results, as few as three

examples of the game are extant. Manufacturers and publishers turned out more than fifty different

tabletop versions of America's new national pastime in just the 19th century alone, introducing almost

every variety of game mechanic short of computers. Baseball cardgames arrived in 1884 with Base Ball

~ A Professional & Social Game of Cards and Lawson's Patent Game ~ Base Ball with Cards.

League Parlor Base Ball by R. Bliss Mfg., also from 1884, was the first dice baseball game.

H H Durgin's "Base Ball Game" -- produced as a promotional item for several companies and

alternatively titled New Base Ball Game -- debuted in 1885 with a simple teetotum to show the result

of each play. Wachter's Parlor Base Ball, manufactured by Columbus Engraving, circa 1890, is

probably the earliest baseball-themed bagatelle game.

League Parlor Base Ball by R. Bliss Mfg., also from 1884, was the first dice baseball game.

H H Durgin's "Base Ball Game" -- produced as a promotional item for several companies and

alternatively titled New Base Ball Game -- debuted in 1885 with a simple teetotum to show the result

of each play. Wachter's Parlor Base Ball, manufactured by Columbus Engraving, circa 1890, is

probably the earliest baseball-themed bagatelle game.

McLoughlin Brothers of New York, the toniest and most successful publisher of boardgames in

the 19th century, were naturally the most prolific in turning out baseball games, and their ornately

chromolithographed boardgames are, today, among those most prized by collectors. Zimmer's

Base Ball Game, an action game in the Buckley/Sebring tradition -- endorsed by Cleveland catcher

Chief Zimmer and decorated with portraits of eighteen star players of the day, half of them now

Hall of Fame inductees -- is among the most elaborate and now rarest numbers from the McLoughlin

line. As few as ten may survive, and the infrequent appearance of one at auction is certain to earn

a five-figure hammer price.

McLoughlin Brothers of New York, the toniest and most successful publisher of boardgames in

the 19th century, were naturally the most prolific in turning out baseball games, and their ornately

chromolithographed boardgames are, today, among those most prized by collectors. Zimmer's

Base Ball Game, an action game in the Buckley/Sebring tradition -- endorsed by Cleveland catcher

Chief Zimmer and decorated with portraits of eighteen star players of the day, half of them now

Hall of Fame inductees -- is among the most elaborate and now rarest numbers from the McLoughlin

line. As few as ten may survive, and the infrequent appearance of one at auction is certain to earn

a five-figure hammer price.

Similarly prized by wealthy collectors -- and an object lesson in why some knowledge of the

variations of any one game is vital for both collectors and vendors -- is the card game Fan Craze.

The Fan Craze Co of Cincinnati published two editions in 1904, each a simple "draw" game with the

sizes of the box and wooden gameboard the only significant differences. Neither is rare today, and

an example of either, complete and in nice condition, can usually be had for less than $250., sometimes

less than $100. Two more editions were published in 1906, now featuring photographic portraits of

star players of the day on each card. These "Art Series" editions -- one with American League

players, one with National Leaguers -- can sell from $5,000. to, in a record-breaking 2005 auction

price, more than $50,000. The reason -- beyond the desirability of the stately portraits -- is that

many card collectors, as distinguished from game collectors, have no respect for the integrity of

the cardgame per se, and engage in the horrid practise of selling off and/or buying individual cards

from the game, some of which can command over $1,000. each. As a result, while the individual

cards are plentiful, complete sets of the "Art Series" editions are now rare indeed.

Games like Zimmer's and Fan Craze, depicting star players, hold a special attraction for

many collectors. The Champion Game of Base Ball, a simple little dual-spinner number made by

A S Schutz in 1889, is another high-priced rarity today, and, with its prominent cover portraits of

Hall of Famers Dan Brouthers and John Clarkson, was among the first, perhaps the very first, to

sport the images of famous players. Through the years, dozens of games have featured the names

and/or likenesses of, been officially endorsed by, and even been designed by major-league players

and managers. Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Bob Feller, each of whom lent their

names to several different games, are among a long list of players, both the celebrated and the

obscure, with their names featured in a game's title.

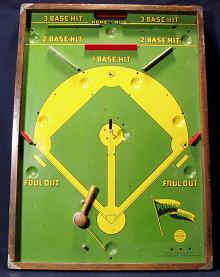

The 20th century saw further innovations in attempting to bring baseball to the tabletop --

special dice featuring more than the standard six sides and/or with unique markings, dense charts

providing more complicated and realistic results, multiple spinners, rotating scroll displays, electrical

elements, and still other occasionally bizarre methods to determine play. Dart and target games

debuted, as did simple dexterity games, and pinball games, both fully mechanized arcade-sized

coin-op tables and simpler versions for play at home. Almost every major manufacturer of games

and toys tried their hand with one or more baseball games -- Parker Brothers, Milton Bradley,

Selchow & Righter, Marx, Ideal, Pressman, Whitman, Warren, Hasbro, Mattel, Gotham, Tudor,

3M, Saalfield, All-Fair, E S Lowe, Avalon Hill, Coleco, Kenner, Transogram, Carrom, Munro...

companies from Kellogg's and Sealtest to Sports Illustrated, Samsonite, and Sears got involved

in turning out baseball games, not to mention an enormous list of obscure, short-lived little one-off

game publishers and even more obscure cottage-industry indies. A significant number and variety

of baseball games were produced by manufacturers in Japan, Canada, Cuba, and elsewhere. By

even the most conservative count -- including only boardgames and cardgames, action games, and

tabletop or handheld bagatelles -- one could justifiably list at minimum more than a thousand distinct

and different tabletop baseball games commercially produced since the 1860s. Including the many

variations in titles, box designs and board graphics, and "season sets" among those games, as well as

hundreds of baseball-themed dexterity games, trivia games, dart, target and toss games, puzzle games,

handheld and tabletop electronic games, and baseball games packaged in "variety games" and boxed

game medleys, that total could probably be doubled.

Similarly prized by wealthy collectors -- and an object lesson in why some knowledge of the

variations of any one game is vital for both collectors and vendors -- is the card game Fan Craze.

The Fan Craze Co of Cincinnati published two editions in 1904, each a simple "draw" game with the

sizes of the box and wooden gameboard the only significant differences. Neither is rare today, and

an example of either, complete and in nice condition, can usually be had for less than $250., sometimes

less than $100. Two more editions were published in 1906, now featuring photographic portraits of

star players of the day on each card. These "Art Series" editions -- one with American League

players, one with National Leaguers -- can sell from $5,000. to, in a record-breaking 2005 auction

price, more than $50,000. The reason -- beyond the desirability of the stately portraits -- is that

many card collectors, as distinguished from game collectors, have no respect for the integrity of

the cardgame per se, and engage in the horrid practise of selling off and/or buying individual cards

from the game, some of which can command over $1,000. each. As a result, while the individual

cards are plentiful, complete sets of the "Art Series" editions are now rare indeed.

Games like Zimmer's and Fan Craze, depicting star players, hold a special attraction for

many collectors. The Champion Game of Base Ball, a simple little dual-spinner number made by

A S Schutz in 1889, is another high-priced rarity today, and, with its prominent cover portraits of

Hall of Famers Dan Brouthers and John Clarkson, was among the first, perhaps the very first, to

sport the images of famous players. Through the years, dozens of games have featured the names

and/or likenesses of, been officially endorsed by, and even been designed by major-league players

and managers. Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Bob Feller, each of whom lent their

names to several different games, are among a long list of players, both the celebrated and the

obscure, with their names featured in a game's title.

The 20th century saw further innovations in attempting to bring baseball to the tabletop --

special dice featuring more than the standard six sides and/or with unique markings, dense charts

providing more complicated and realistic results, multiple spinners, rotating scroll displays, electrical

elements, and still other occasionally bizarre methods to determine play. Dart and target games

debuted, as did simple dexterity games, and pinball games, both fully mechanized arcade-sized

coin-op tables and simpler versions for play at home. Almost every major manufacturer of games

and toys tried their hand with one or more baseball games -- Parker Brothers, Milton Bradley,

Selchow & Righter, Marx, Ideal, Pressman, Whitman, Warren, Hasbro, Mattel, Gotham, Tudor,

3M, Saalfield, All-Fair, E S Lowe, Avalon Hill, Coleco, Kenner, Transogram, Carrom, Munro...

companies from Kellogg's and Sealtest to Sports Illustrated, Samsonite, and Sears got involved

in turning out baseball games, not to mention an enormous list of obscure, short-lived little one-off

game publishers and even more obscure cottage-industry indies. A significant number and variety

of baseball games were produced by manufacturers in Japan, Canada, Cuba, and elsewhere. By

even the most conservative count -- including only boardgames and cardgames, action games, and

tabletop or handheld bagatelles -- one could justifiably list at minimum more than a thousand distinct

and different tabletop baseball games commercially produced since the 1860s. Including the many

variations in titles, box designs and board graphics, and "season sets" among those games, as well as

hundreds of baseball-themed dexterity games, trivia games, dart, target and toss games, puzzle games,

handheld and tabletop electronic games, and baseball games packaged in "variety games" and boxed

game medleys, that total could probably be doubled.

National Pastime, designed by Clifford Van Beek and published by Major Games in 1930, was

a milestone in the development of tabletop baseball. Using a combination of dice and individualized

cards, it was the first game to attempt to simulate the individual performance of real-life players.

In every game that had come before, every name in your line-up had the exact same chance of hitting

a single or a home run or striking out as every other name in the line-up, dependent only on the roll

of the dice, the spin of the spinner, the draw of the card. Van Beek translated real-life statistics to

each player card in his game, so now, right there on your tabletop just like in real life, Babe Ruth and

Jimmie Foxx would bash tons of home runs, draw loads of walks, and strike out plenty, while Paul

Waner would rip mainly singles and doubles and almost never whiff. It was a major breakthrough,

but the Great Depression killed the little indie company and Van Beek's game almost before it saw

the light of day.

National Pastime, designed by Clifford Van Beek and published by Major Games in 1930, was

a milestone in the development of tabletop baseball. Using a combination of dice and individualized

cards, it was the first game to attempt to simulate the individual performance of real-life players.

In every game that had come before, every name in your line-up had the exact same chance of hitting

a single or a home run or striking out as every other name in the line-up, dependent only on the roll

of the dice, the spin of the spinner, the draw of the card. Van Beek translated real-life statistics to

each player card in his game, so now, right there on your tabletop just like in real life, Babe Ruth and

Jimmie Foxx would bash tons of home runs, draw loads of walks, and strike out plenty, while Paul

Waner would rip mainly singles and doubles and almost never whiff. It was a major breakthrough,

but the Great Depression killed the little indie company and Van Beek's game almost before it saw

the light of day.

It would be ten years before another attempt was made to replicate real-life player performance

in a tabletop game, but this time it resulted in one of the great successes in boardgame history. Ethan

Allen, a longtime major-league outfielder with several clubs, later Yale's baseball coach and author of

several books on the game's strategy and mechanics, developed a system which translated individual

player performance to a sort of pie-chart, the size of each wedge corresponding to each player's

tendencies -- big "home run" wedges for power hitters, for example, small ones for slap hitters, more

"hit" wedges for high-average batters, fewer for weaker hitters, and so on. Cadaco-Ellis produced

the game, beginning in 1941, and Ethan Allen's All-Star Baseball, with several variations to the title

and graphics, went on to be a big hit for more than fifty years. New sets of player "disks," featuring

updated stats and different players, were issued each season. Legions of fans still play the game and

avidly collect vintage "ASB" games and disk sets, and have created sets of player disks for seasons

before 1941 and beyond 1993, as well as engineering endless modifications to the game, including

sophisticated pitching systems. ASB enthusiasts have an outstanding on-line forum for their game.

A tip for anyone selling an edition of ASB: many vendors of vintage examples of the game make the

mistake of thinking the copyright date on the game box indicates which season set it contains, but

the copyright remained the same while the sets of player disks changed annually. The CadacoASB

Forum provides a file for identifying which season's set you have, but ASB collectors can identify

a set if just the last names of just the pitchers are listed in an auction description.

Van Beek's National Pastime did find at least one avid fan, and twenty years later, Richard

Seitz, who played that game as a boy and derived from it a game of his own, put his reworking of

National Pastime on the market. The game was APBA Major League Baseball, and it soon

rivalled and eventually surpassed ASB in popularity as a major-league simulation. Like ASB, APBA

turned out a new set of player cards each year, but with much larger rosters. Through several name

changes and alongside several other APBA sports games, APBA Baseball is still going strong after

sixty years, and many past season sets of player cards are collectors' items for APBA aficionados.

It would be ten years before another attempt was made to replicate real-life player performance

in a tabletop game, but this time it resulted in one of the great successes in boardgame history. Ethan

Allen, a longtime major-league outfielder with several clubs, later Yale's baseball coach and author of

several books on the game's strategy and mechanics, developed a system which translated individual

player performance to a sort of pie-chart, the size of each wedge corresponding to each player's

tendencies -- big "home run" wedges for power hitters, for example, small ones for slap hitters, more

"hit" wedges for high-average batters, fewer for weaker hitters, and so on. Cadaco-Ellis produced

the game, beginning in 1941, and Ethan Allen's All-Star Baseball, with several variations to the title

and graphics, went on to be a big hit for more than fifty years. New sets of player "disks," featuring

updated stats and different players, were issued each season. Legions of fans still play the game and

avidly collect vintage "ASB" games and disk sets, and have created sets of player disks for seasons

before 1941 and beyond 1993, as well as engineering endless modifications to the game, including

sophisticated pitching systems. ASB enthusiasts have an outstanding on-line forum for their game.

A tip for anyone selling an edition of ASB: many vendors of vintage examples of the game make the

mistake of thinking the copyright date on the game box indicates which season set it contains, but

the copyright remained the same while the sets of player disks changed annually. The CadacoASB

Forum provides a file for identifying which season's set you have, but ASB collectors can identify

a set if just the last names of just the pitchers are listed in an auction description.

Van Beek's National Pastime did find at least one avid fan, and twenty years later, Richard

Seitz, who played that game as a boy and derived from it a game of his own, put his reworking of

National Pastime on the market. The game was APBA Major League Baseball, and it soon

rivalled and eventually surpassed ASB in popularity as a major-league simulation. Like ASB, APBA

turned out a new set of player cards each year, but with much larger rosters. Through several name

changes and alongside several other APBA sports games, APBA Baseball is still going strong after

sixty years, and many past season sets of player cards are collectors' items for APBA aficionados.

Other major-league sim games followed. Big League Manager debuted in 1955, initially

produced by Arrowhead Industries, later by Big League Co; Negamco's Major League Baseball

was introduced in 1959. Both games were devised by, and both companies run by, the Henricksen

brothers, and both games are still, if somewhat erratically, in production, and have their own loyal

followings. More sophisticated "generic" games emerged as well, notably Tom Shaw's Baseball

Strategy, originally from Strategy Game Co Inc, in 1958, and then produced from 1960 to 1984

by Avalon Hill and Sports Illustrated.

Other major-league sim games followed. Big League Manager debuted in 1955, initially

produced by Arrowhead Industries, later by Big League Co; Negamco's Major League Baseball

was introduced in 1959. Both games were devised by, and both companies run by, the Henricksen

brothers, and both games are still, if somewhat erratically, in production, and have their own loyal

followings. More sophisticated "generic" games emerged as well, notably Tom Shaw's Baseball

Strategy, originally from Strategy Game Co Inc, in 1958, and then produced from 1960 to 1984

by Avalon Hill and Sports Illustrated.

The leviathan of major-league sims arose in 1961 -- Hal Richman's Strat-O-Matic Baseball

would, within a few years, surpass all its competitors and become the best-selling sports boardgame

of all time. A complex combination of dice, charts, and player cards, Strat-O-Matic -- "Strat,"

"Strat-O," or "S-O-M" to its fervid devotees -- employs an innovative and intricately calculated

"split" system, with some results coming off "hitter" cards and others read from the "pitcher" cards.

As with APBA, Strat-O-Matic also produces sims for sports other than baseball, and original

editions of many of its past season sets, too, are collectors items.

The leviathan of major-league sims arose in 1961 -- Hal Richman's Strat-O-Matic Baseball

would, within a few years, surpass all its competitors and become the best-selling sports boardgame

of all time. A complex combination of dice, charts, and player cards, Strat-O-Matic -- "Strat,"

"Strat-O," or "S-O-M" to its fervid devotees -- employs an innovative and intricately calculated

"split" system, with some results coming off "hitter" cards and others read from the "pitcher" cards.

As with APBA, Strat-O-Matic also produces sims for sports other than baseball, and original

editions of many of its past season sets, too, are collectors items.

Still more sims were to come, some with radically different play mechanics, others with subtle

variations on their predecessors. Among the most popular and/or most highly regarded by gamers

have been Sy Marder's Be A Manager, produced by Bamco in 1967 with later editions through 1972;

SherCo's Baseball Simulation -- later SherCo II and most recently SherCo Grand Slam Baseball

-- designed by Steven LeShay, which debuted in 1968; David Neft's Baseball, published by Sports

Illustrated in 1971, and its later variations, Baseball Game, All-Time All-Star Baseball, and

Superstar Baseball!; Major League Baseball Game and All-Time Greats Baseball Game,

designed by Jim Barnes and published by Midwest Research Inc around 1971, but later famously

renamed Statis Pro Baseball, published, in several variations, until 1993 by Avalon Hill and

Sports Illustrated; Replay Games Major League Baseball Games, designed by Norm Roth and

John Brodak, which first appeared briefly in 1973, re-emerged briefly again in 1989, then found

its greatest success after being revised and reintroduced by Pete Ventura in 2000; George Gerney's

ASG Major League Baseball of 1973-74, revised and reissued in 1989; Jack Kavanaugh's 1970s

Extra Innings Baseball Game from Gamecraft, republished by Big League Co since 2003; and

Mike Cieslinski's fantastically detailed and hugely popular Dynasty League Baseball, originally titled

Pursue the Pennant when it debuted in 1985 and regarded by many as the ultimate in baseball sims.

There were dozens more, not even including several entirely new games that debut every year -- most,

if not all, issued with new sets of player statistics each spring, and each the "only" game for most of

their adherents, many of whom often play out hundreds of games a year to re-enact an entire baseball

season.

Still more sims were to come, some with radically different play mechanics, others with subtle

variations on their predecessors. Among the most popular and/or most highly regarded by gamers

have been Sy Marder's Be A Manager, produced by Bamco in 1967 with later editions through 1972;

SherCo's Baseball Simulation -- later SherCo II and most recently SherCo Grand Slam Baseball

-- designed by Steven LeShay, which debuted in 1968; David Neft's Baseball, published by Sports

Illustrated in 1971, and its later variations, Baseball Game, All-Time All-Star Baseball, and

Superstar Baseball!; Major League Baseball Game and All-Time Greats Baseball Game,

designed by Jim Barnes and published by Midwest Research Inc around 1971, but later famously

renamed Statis Pro Baseball, published, in several variations, until 1993 by Avalon Hill and

Sports Illustrated; Replay Games Major League Baseball Games, designed by Norm Roth and

John Brodak, which first appeared briefly in 1973, re-emerged briefly again in 1989, then found

its greatest success after being revised and reintroduced by Pete Ventura in 2000; George Gerney's

ASG Major League Baseball of 1973-74, revised and reissued in 1989; Jack Kavanaugh's 1970s

Extra Innings Baseball Game from Gamecraft, republished by Big League Co since 2003; and

Mike Cieslinski's fantastically detailed and hugely popular Dynasty League Baseball, originally titled

Pursue the Pennant when it debuted in 1985 and regarded by many as the ultimate in baseball sims.

There were dozens more, not even including several entirely new games that debut every year -- most,

if not all, issued with new sets of player statistics each spring, and each the "only" game for most of

their adherents, many of whom often play out hundreds of games a year to re-enact an entire baseball

season.

The rise of the "MLB sims," however, did not end or even slow the production of "generic"

baseball games, which continued to be invented and re-invented in hundreds of forms, and continued

in popularity, throughout the 20th century. One particularly notable long-lasting example, and one of

historic importance in the hobby, is Our National Ball Game, patented and sold by McGill & Delany

in 1887. Their innovative two-dice system was used without alteration for several Parker Brothers

baseball games of the 1890s and early 1900s, again in Parkers' long-running "combination game" sets

from 1926 into the 1960s, and still again in their 1950s and '60s editions of Game of Peg Baseball

(an entirely different game than their earlier Peg Baseball, produced from 1908 into the 1940s).

Further, McGill & Delany's system -- requiring little more than a pair of dice and some memorization

of the results of the 21 combinations -- was the foundation for untold numbers of "home brew" games,

played by thousands of kids over the past 120 years, handed down from one generation to the next,

with no need of a gameboard.

Nor has the evolution and popularity of MLB sims ended the development of generic games,

which, like the MLB sims, continue to arrive annually in new forms from different manufacturers and

publishers. Nor have modern sims diminished the old games' appeal among collectors and researchers.

Hobbyists with a serious interest in the history of the games continue to discover rare examples of

obscure antique baseball games never before catalogued, and to investigate the intriguing stories of the

long-vanished companies that produced them and the long-forgotten inventors who designed them.

If many boardgamers who may have dismissed the genre of tabletop sports games take a closer look,

they'll find the variety and ingenuity of the game engines an eye-opener, and baseball fans somehow

unfamiliar with tabletop versions of their sport should be enthralled by the baseball history manifest

in the 150-year parade of tabletop games.

The rise of the "MLB sims," however, did not end or even slow the production of "generic"

baseball games, which continued to be invented and re-invented in hundreds of forms, and continued

in popularity, throughout the 20th century. One particularly notable long-lasting example, and one of

historic importance in the hobby, is Our National Ball Game, patented and sold by McGill & Delany

in 1887. Their innovative two-dice system was used without alteration for several Parker Brothers

baseball games of the 1890s and early 1900s, again in Parkers' long-running "combination game" sets

from 1926 into the 1960s, and still again in their 1950s and '60s editions of Game of Peg Baseball

(an entirely different game than their earlier Peg Baseball, produced from 1908 into the 1940s).

Further, McGill & Delany's system -- requiring little more than a pair of dice and some memorization

of the results of the 21 combinations -- was the foundation for untold numbers of "home brew" games,

played by thousands of kids over the past 120 years, handed down from one generation to the next,

with no need of a gameboard.

Nor has the evolution and popularity of MLB sims ended the development of generic games,

which, like the MLB sims, continue to arrive annually in new forms from different manufacturers and

publishers. Nor have modern sims diminished the old games' appeal among collectors and researchers.

Hobbyists with a serious interest in the history of the games continue to discover rare examples of

obscure antique baseball games never before catalogued, and to investigate the intriguing stories of the

long-vanished companies that produced them and the long-forgotten inventors who designed them.

If many boardgamers who may have dismissed the genre of tabletop sports games take a closer look,

they'll find the variety and ingenuity of the game engines an eye-opener, and baseball fans somehow

unfamiliar with tabletop versions of their sport should be enthralled by the baseball history manifest

in the 150-year parade of tabletop games.

-- text copyright 2011, 2019 by the Baseball Games front office staff --

-- text copyright 2011, 2019 by the Baseball Games front office staff --

This page is heavy with photos and may cause problems for users with slow connections.

If photos do not load, PC users should right-click the red "X," then click "Show Picture,"

or simply try reloading page.

-- Updated August 2019 --

|