McLoughlin Bros., Inc. was a New York publishing firm, especially notable for pioneering the systematic use of color

printing technologies in children's books during the latter half of the 19th century.

The company began in 1828 when Scottish coachmaker-turned-printer John McLoughlin Sr opened his own printing concern

on New York City's Tryon Row (now the last block of Centre Street before it becomes Park Row). He wrote and published

a series of semi-religious tracts titled McLoughlin's Books for Children. In 1840, he partnered with engraver and printer

Robert H Elton to form Elton & Co., publishing toy books, comic almanacs, and valentines.

In his teens, John McLoughlin Jr (1827-1905) learned wood engraving and printing while apprenticing for the company

run by his father and Elton. By 1851, McLoughlin Sr and Elton had retired, giving John Jr control of the business, which he

renamed John McLoughlin, Successor to Elton & Co. He started to publish picture books with that imprint, and soon acquired

the printing blocks of Edward Dunigan, a New York picture-book publisher for whom Elton had executed many wood engravings.

After a fire destroyed the Tryon Row operation, the company relocated to 24 Beekman Street (now the back of 8 Spruce)

in lower Manhattan. According to McLoughlin Jr's obituary in Publishers' Weekly (6 May 1905), he made his younger brother

Edmund McLoughlin (1833 or '34 - 1889) a partner in 1855. However, the firm was not listed in New York city directories as

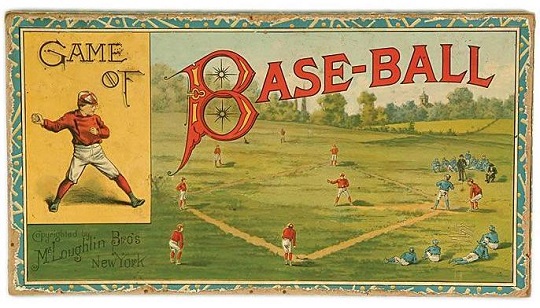

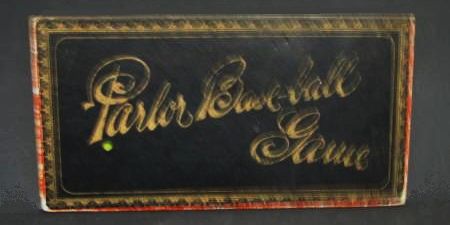

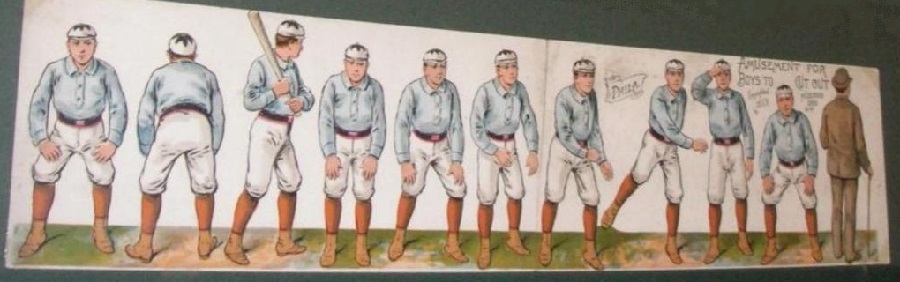

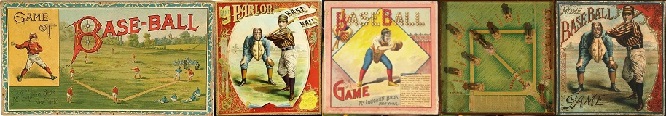

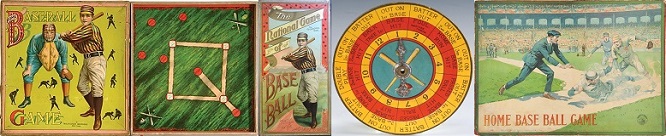

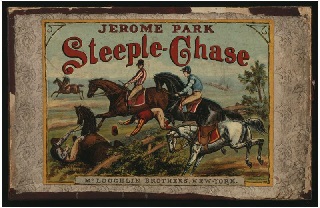

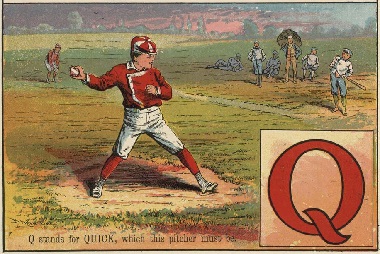

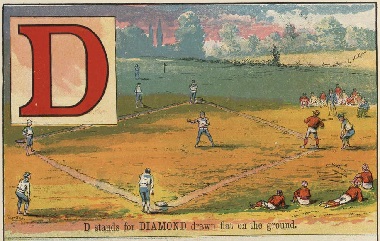

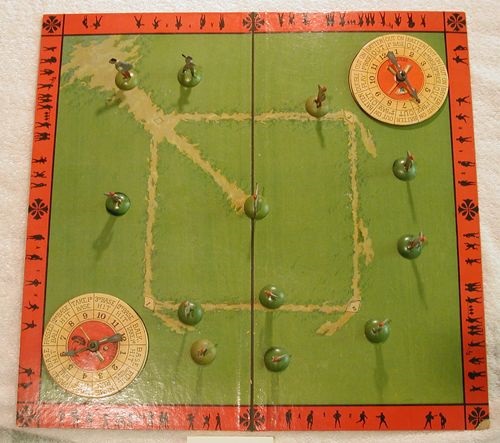

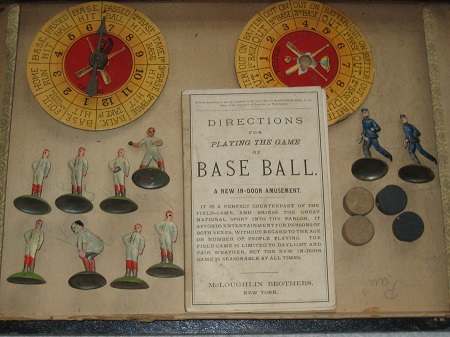

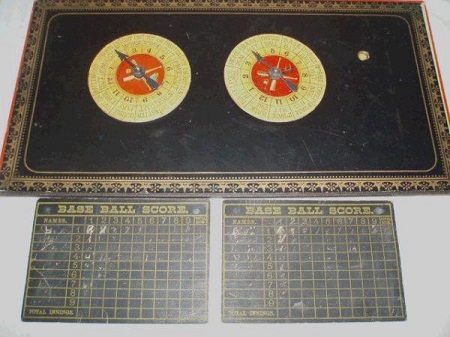

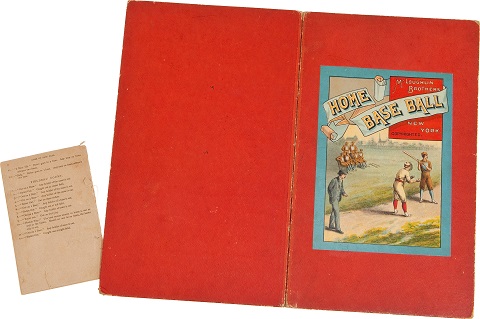

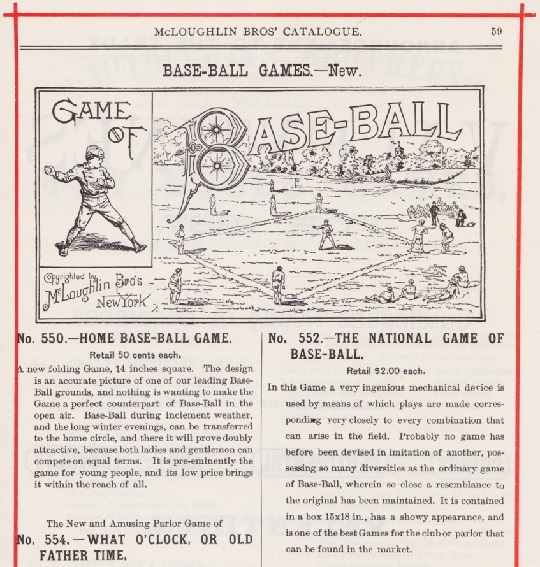

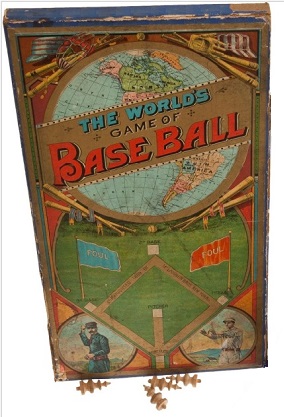

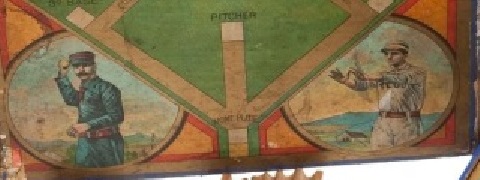

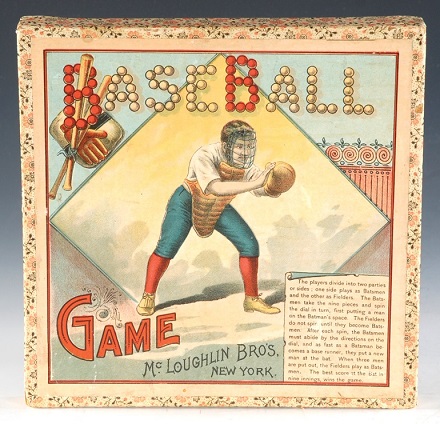

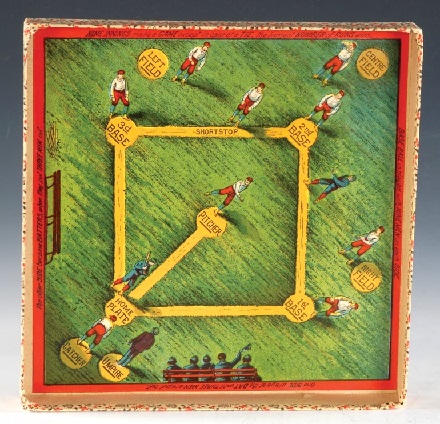

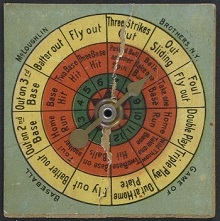

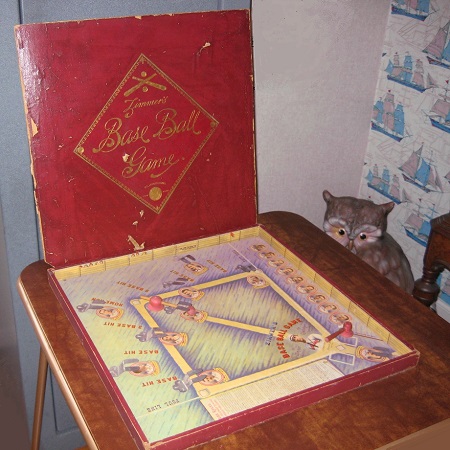

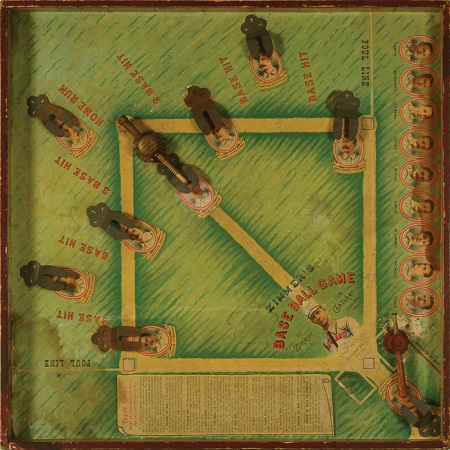

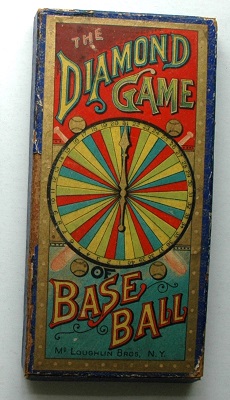

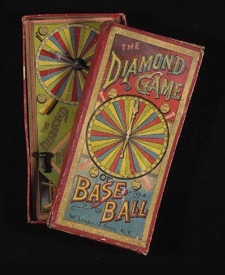

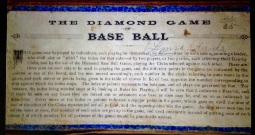

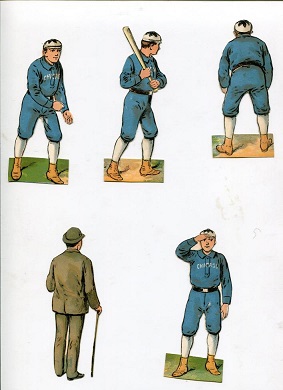

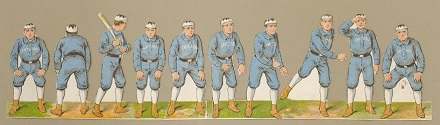

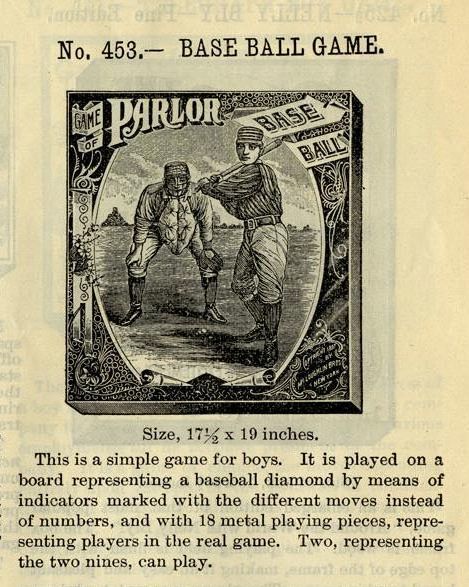

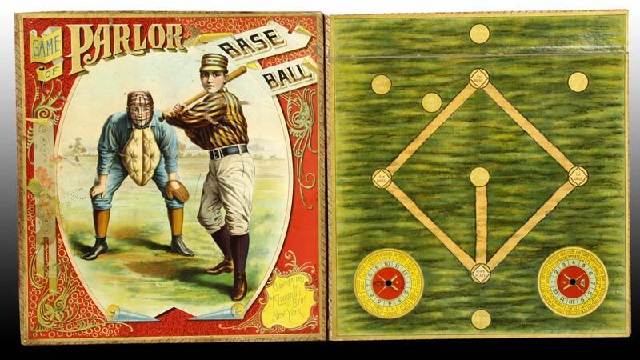

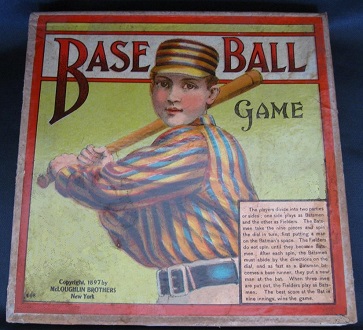

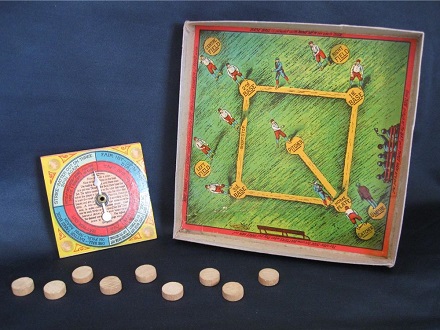

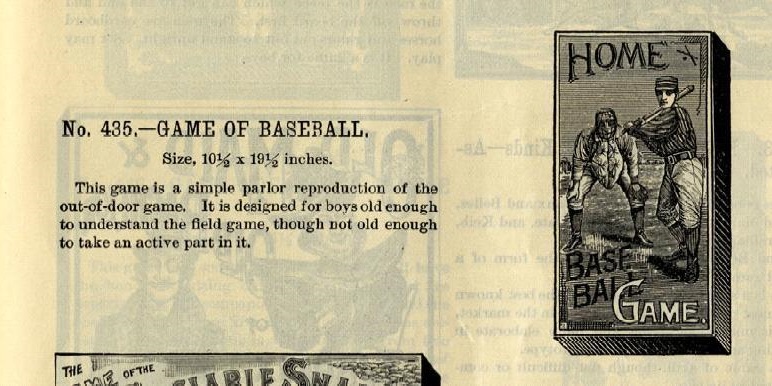

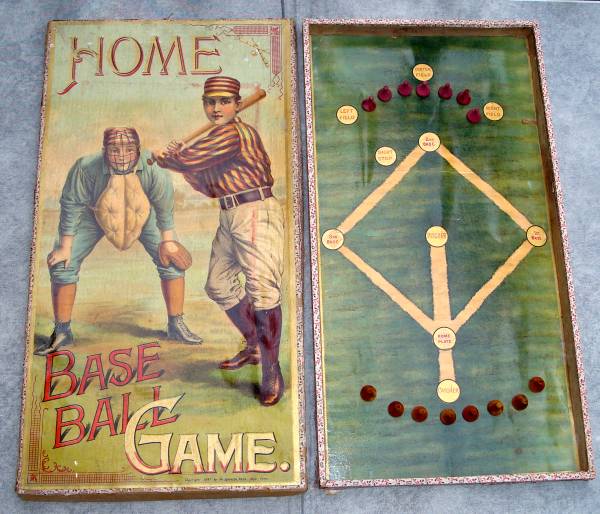

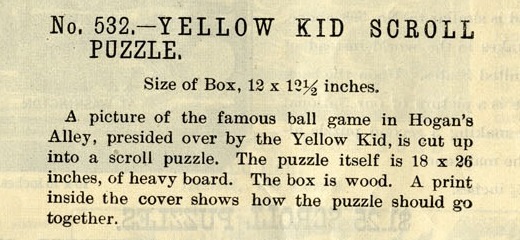

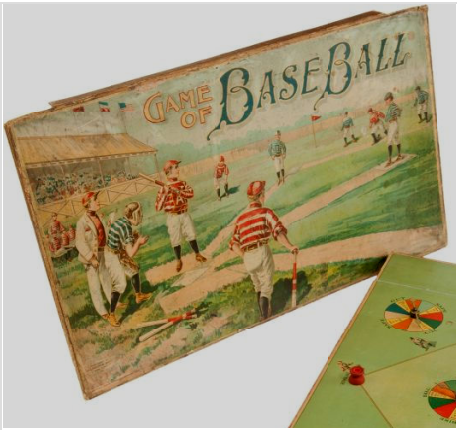

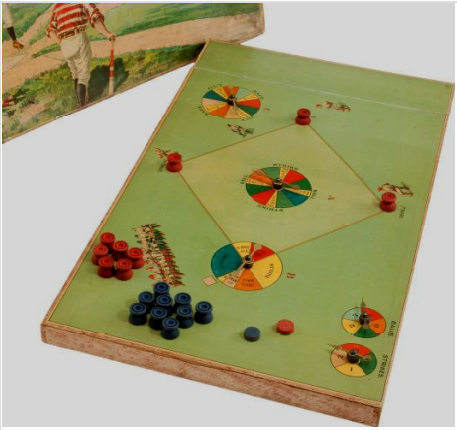

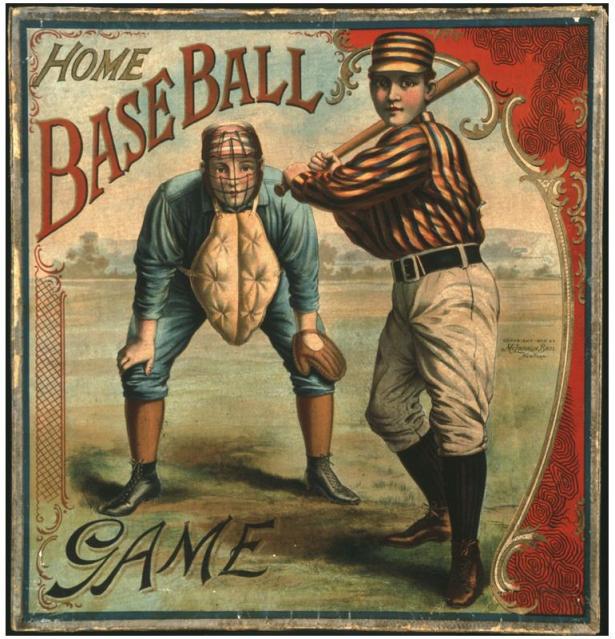

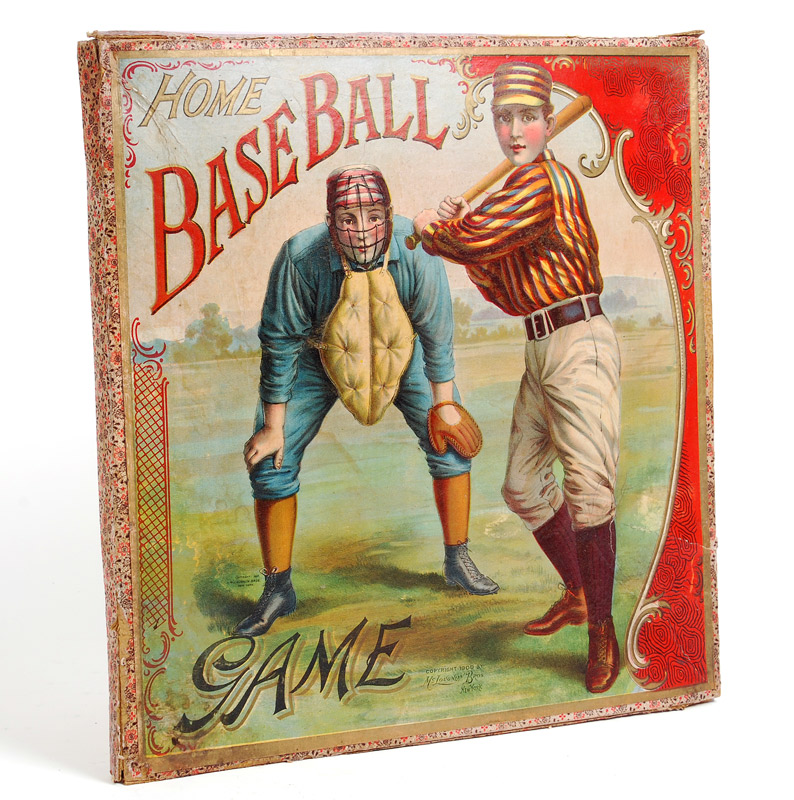

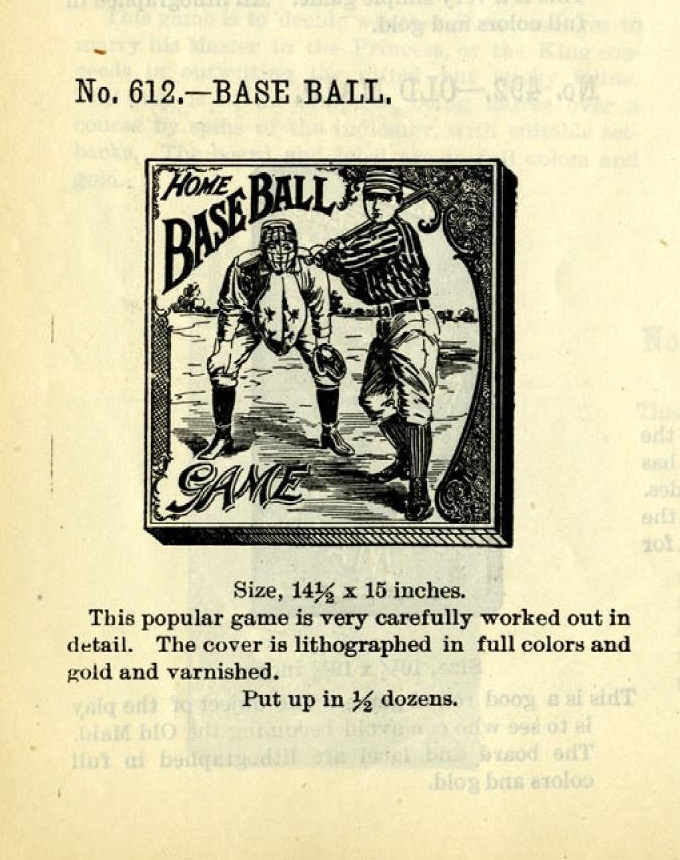

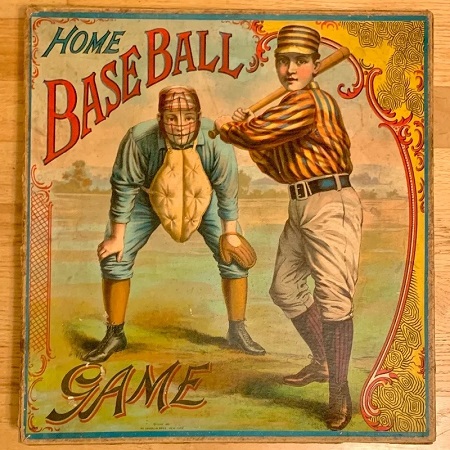

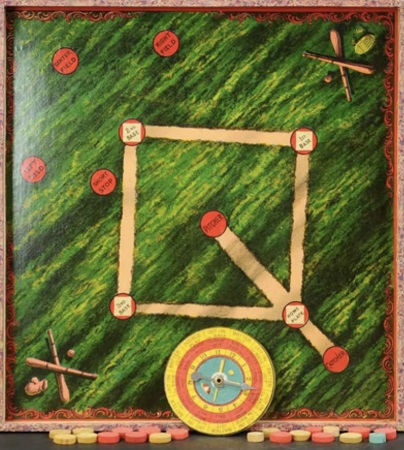

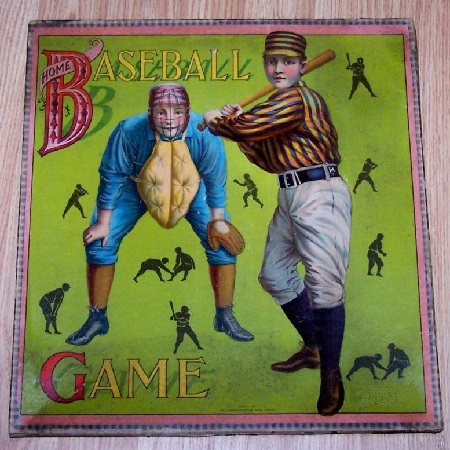

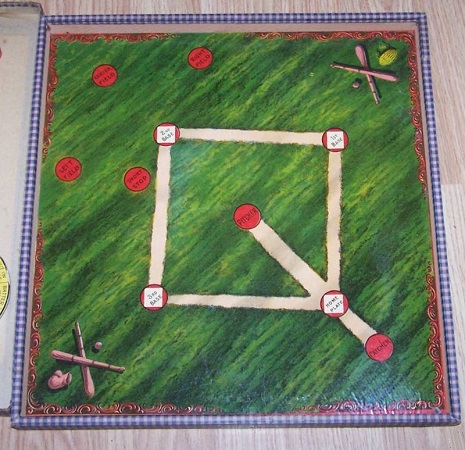

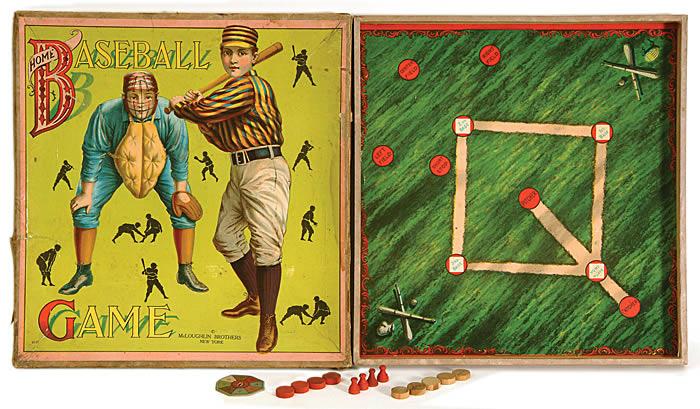

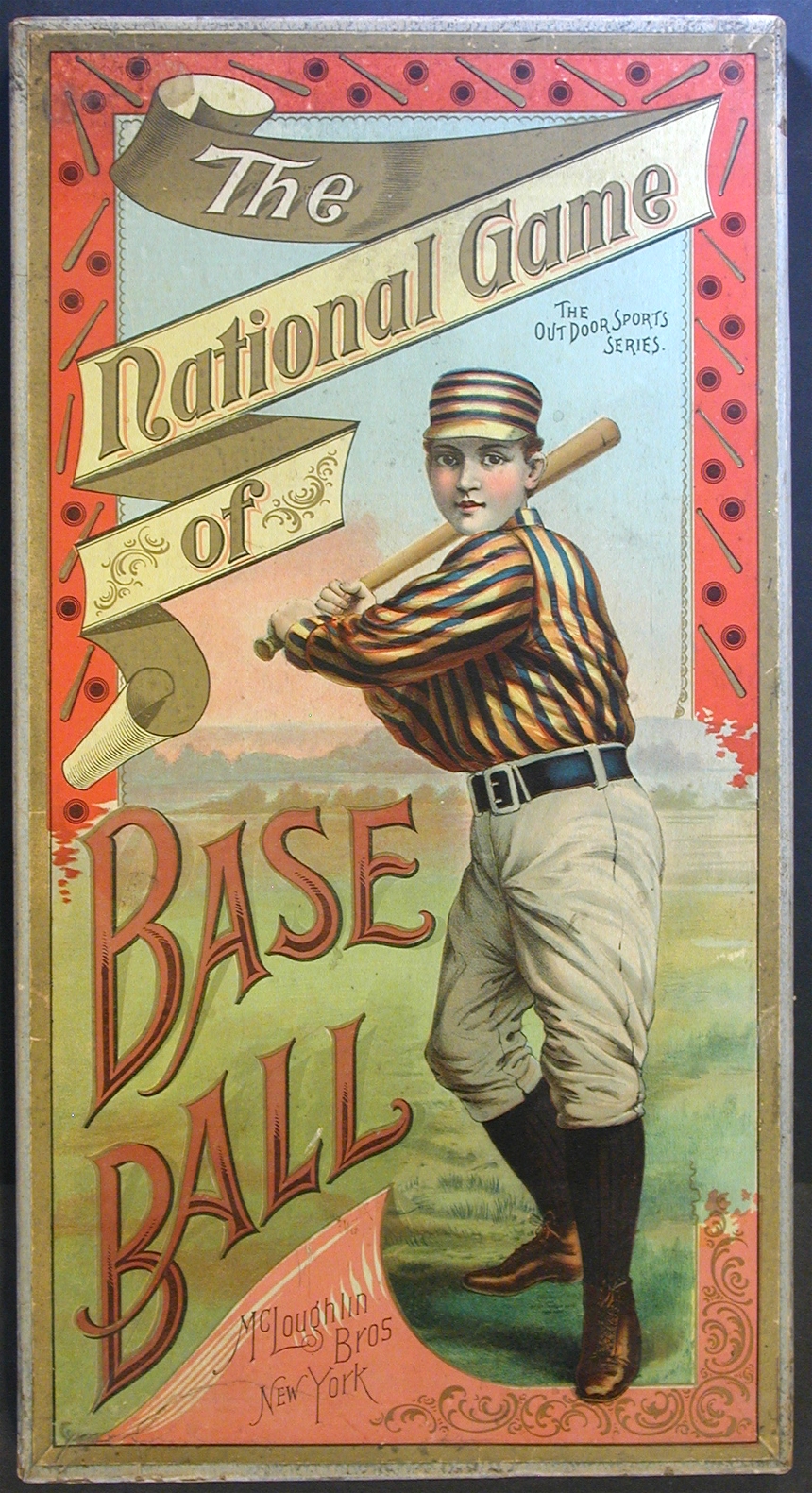

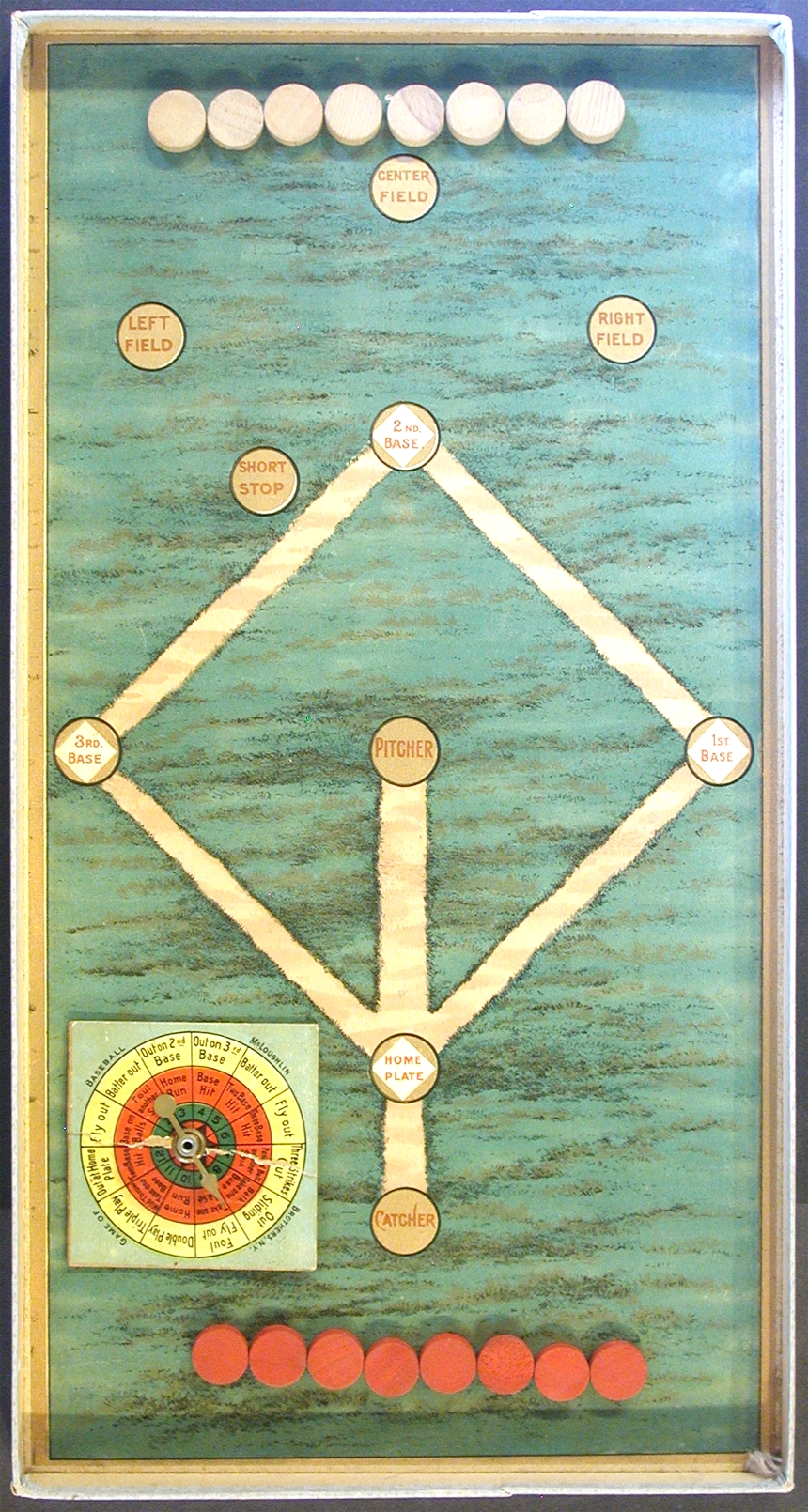

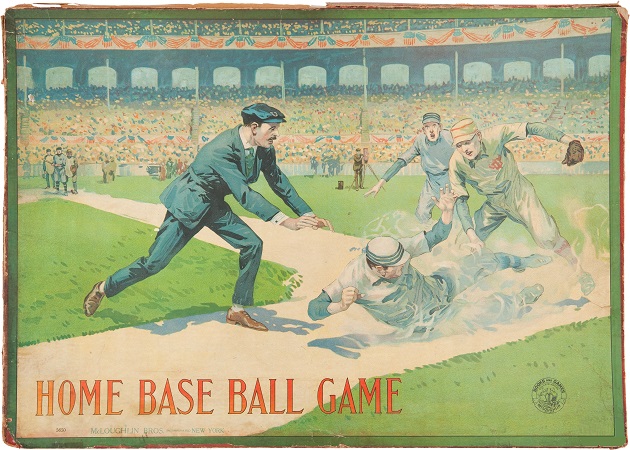

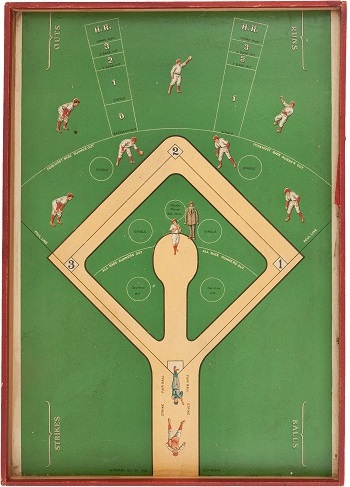

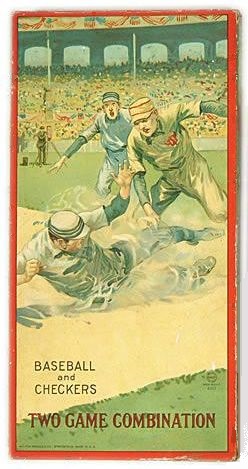

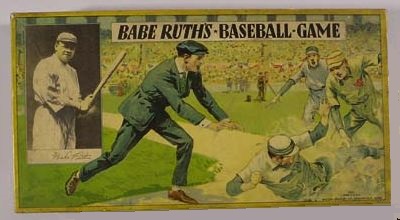

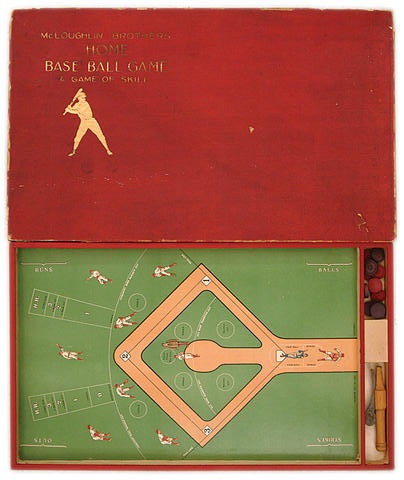

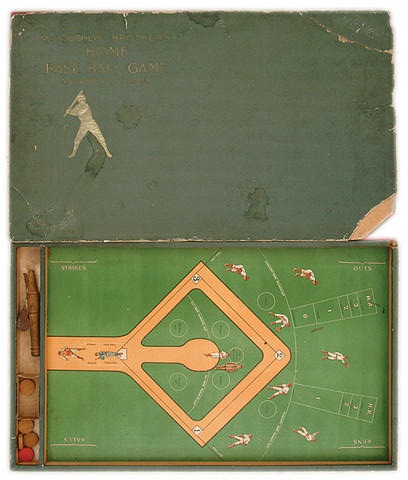

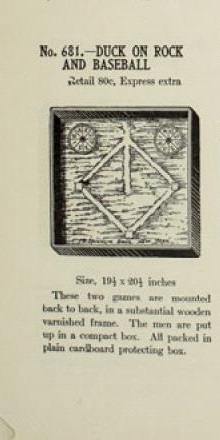

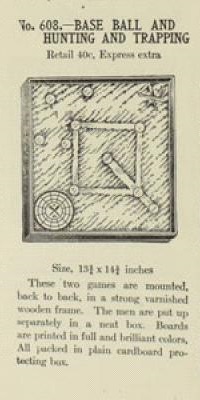

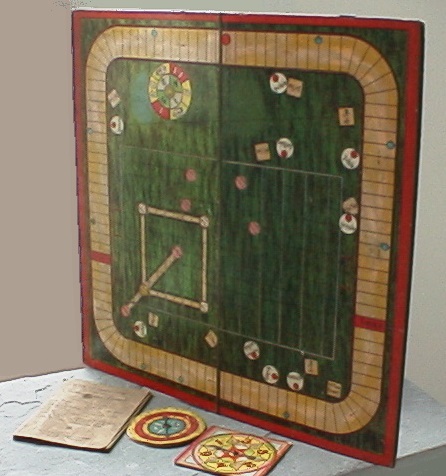

McLoughlin Bros. until 1858. During the early years of this partnership, the product line expanded to include games, wooden

toy blocks, and paper dolls. By 1863, the firm had expanded its headquarters at 24 Beekman Street as well, to include

30 Beekman.

Foreign books were not then protected by United States copyright, so McLoughlin reprinted British books in a cheaper

format, introducing to American children the work of illustration greats like Walter Crane, Randolph Caldecott, and Kate

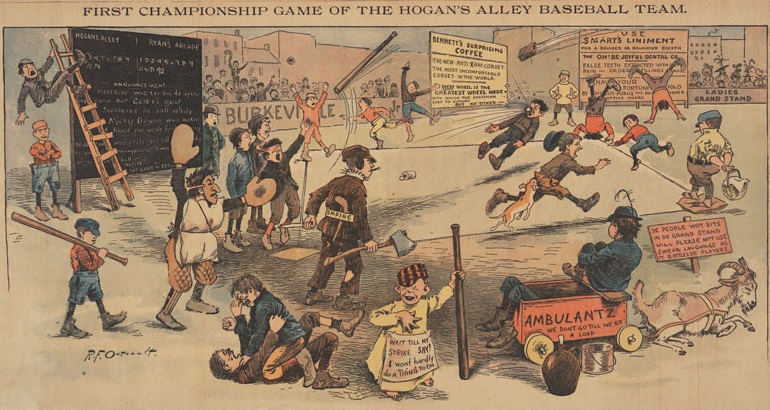

Greenaway. After the Civil War, McLoughlin Brothers acquired their own illustrators, and helped popularize the work of

artists including Thomas Nast, William Momberger, Justin H Howard, Palmer Cox, and Ida Waugh.

John McLoughlin Jr continually experimented with color illustration -- progressing from hand stenciling, to the mechanical

relief process of zinc etching, to the planographic process of chromolithography. The company's commercial and creative

development found McLoughlin Bros. relocating to 52 Greene Street (just south of Broome) in May 1870. In February 1871,

they opened their main office at 71 Duane Street (between Broadway and what is now Thomas Paine Park), and a color

printing plant in Brooklyn at 65 South 11th Street (corner of Berry). This factory -- at that time, the largest color printing

factory in the United States -- employed as many as 75 artists, and is the probable site of the firm's experimentation with

color reproduction techniques. McLoughlin introduced the photographic process which produced the illustration directly on

a zinc plate, with oil colors then being applied to the plate.

By the 1880s, McLoughlin books regularly featured titles in folio formats, illustrated by chromolithographs. A number

of titles were probably "pirate" editions of picture books issued in England by firms such as George Routledge & Sons.

Edmund McLoughlin retired in 1885, and the firm's Manhattan office moved several times over the next twenty years --

623 Broadway (1886-c1892, between Houston and Bleecker, next to the Cable Building -- look up!); 874 Broadway

(1892-1898, northeast corner of East 18th); and 890 Broadway (1899-c1920, next to what's now Loew's 19th Street East).

After Edmund's retirement, the business took on a third generation when John McLoughlin Jr's sons, James Gregory and

Charles, joined the firm. By 1886, the company published a wide range of items including cheap chapbooks, large folio

picture books, linen books, puzzles, games, and paper dolls -- the number, variety, and quality of their games exceeding

those of their major rivals, Milton Bradley, Parker Brothers, and Selchow & Righter.

After John McLoughlin Jr's death in 1905, the company suffered from the loss of his artistic and commercial leadership.

By 1919, his sons had retired or died as well, and H F Stewart was listed as president, with Gregory McLoughlin, son of

James Gregory McLoughlin, as vice president.

In 1920, McLoughlin Bros., Inc. was sold to Milton Bradley, the Brooklyn factory was closed, and the company was

moved to Springfield Massachusetts. With this sale, McLoughlin Bros. ceased game production, although the publication of

picture books continued. McLoughlin Bros. enjoyed some success in the 1930s with mechanical paper toys called "Jolly

Jump-Ups," but the McLoughlin division of Milton Bradley stopped production during World War II.

A 1955 flood severely damaged the Springfield plant, destroying many of the McLoughlin company records, but an archival

collection of McLoughlin Bros. materials had been assembled by company Vice President Charles Ernest Miller (1869-1951).

Between 1950 and 1951, with the firm in the process of being sold or liquidated, the McLoughlin Bros. executive officers

divided among themselves the firm's archival collection of books, drawings, company correspondence, illustration blocks,

paper dolls, freestanding wooden dolls, puzzles, and games. After Miller's death on 4 March 1951, this archival collection

was held by Miller's daughter, Ruth Miller. In December 1951, the McLoughlin Bros. trademark was sold to New York

toy manufacturer Julius Kushner. Under Kushner's leadership, some popular favorites like the Jolly Jump-Ups were reissued.

However, the McLoughlin line of children's books was sold to Grosset & Dunlap in June 1954. Subsequently, several books

bearing the McLoughlin Bros. imprint were issued, but the name dropped out of print by the 1970s.

In 1968, Ruth Miller sold the archival collection to collector Herbert H Hosmer. In 1978, Hosmer donated the collection

to the American Antiquarian Society.

Another significant mass of McLoughlin materials -- manuscripts, typescripts, galleys, correspondence, photographs,

dummies, illustrations, color separations, proofs, samples, mock-ups, blank books, and production material, dating from

1854 to the early 1950s -- is organized as The McLoughlin Brothers Papers, part of the de Grummond Children's Literature

Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi. It includes the work of artists and engravers such as Edward Cogger,

William Momberger, Robert Graef, H G Nicholas, and Johnny Gruelle, among others.

After John McLoughlin Jr's death in 1905, the company suffered from the loss of his artistic and commercial leadership.

By 1919, his sons had retired or died as well, and H F Stewart was listed as president, with Gregory McLoughlin, son of

James Gregory McLoughlin, as vice president.

In 1920, McLoughlin Bros., Inc. was sold to Milton Bradley, the Brooklyn factory was closed, and the company was

moved to Springfield Massachusetts. With this sale, McLoughlin Bros. ceased game production, although the publication of

picture books continued. McLoughlin Bros. enjoyed some success in the 1930s with mechanical paper toys called "Jolly

Jump-Ups," but the McLoughlin division of Milton Bradley stopped production during World War II.

A 1955 flood severely damaged the Springfield plant, destroying many of the McLoughlin company records, but an archival

collection of McLoughlin Bros. materials had been assembled by company Vice President Charles Ernest Miller (1869-1951).

Between 1950 and 1951, with the firm in the process of being sold or liquidated, the McLoughlin Bros. executive officers

divided among themselves the firm's archival collection of books, drawings, company correspondence, illustration blocks,

paper dolls, freestanding wooden dolls, puzzles, and games. After Miller's death on 4 March 1951, this archival collection

was held by Miller's daughter, Ruth Miller. In December 1951, the McLoughlin Bros. trademark was sold to New York

toy manufacturer Julius Kushner. Under Kushner's leadership, some popular favorites like the Jolly Jump-Ups were reissued.

However, the McLoughlin line of children's books was sold to Grosset & Dunlap in June 1954. Subsequently, several books

bearing the McLoughlin Bros. imprint were issued, but the name dropped out of print by the 1970s.

In 1968, Ruth Miller sold the archival collection to collector Herbert H Hosmer. In 1978, Hosmer donated the collection

to the American Antiquarian Society.

Another significant mass of McLoughlin materials -- manuscripts, typescripts, galleys, correspondence, photographs,

dummies, illustrations, color separations, proofs, samples, mock-ups, blank books, and production material, dating from

1854 to the early 1950s -- is organized as The McLoughlin Brothers Papers, part of the de Grummond Children's Literature

Collection at the University of Southern Mississippi. It includes the work of artists and engravers such as Edward Cogger,

William Momberger, Robert Graef, H G Nicholas, and Johnny Gruelle, among others.

|

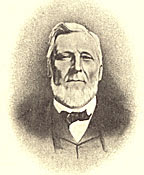

John McLoughlin Jr

John McLoughlin Jr